https://ansionnachfionn.com/seanchas-mythology/tuatha-de-danann/

Tuatha Dé Danann – Cairn Loch Craobh, Sliabh na Caillí, Loch Craobh, An Mhí, Cúige Laighean, Éire (Íomhá: An Sionnach Fionn 2009)

Tuatha Dé Danann – Cairn Loch Craobh, Sliabh na Caillí, Loch Craobh, An Mhí, Cúige Laighean, Éire (Íomhá: An Sionnach Fionn 2009)Tuatha Dé Danann

Introduction

The Tuatha Dé Danann or “Peoples of the Goddess Dana” are a race of supernatural beings in the native mythological and folkloric traditions of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. They incorporate within their stories many of the deities and associated beliefs of the Gaelic nations of north-western Europe before the introduction of Christianity in the 4th and 5th centuries CE. For over a thousand years the Tuatha Dé and their literary derivatives were central to the intellectual creativity of the Gaels; that is the Irish, Scots and Manx. Their influence has endured into the modern era, albeit greatly debased and diluted, and is still to be found in some contemporary works of fiction, drama and art.

Origins

From the 4th to 6th centuries CE a proselytizing movement of Christian missionaries and their successors gradually established a number of churches and monasteries across “pagan” Ireland, usually in the unclaimed or contested wilderness regions between the principal kingdoms and territories of the island. Over the following generations several of these institutions grew into large and propertied religious communities, relying on the patronage of neighbouring aristocratic dynasties for their prosperity. By the late 700s CE these “monastic-towns” had developed schools of learning where ecclesiastical and secular texts in Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Irish were being written, taught and studied. These studies included attempts to reconcile the indigenous traditions of the previously illiterate and non-Christian Gaels with the teachings of the Medieval Church. This eventually gave birth to a body of histories and genealogies which subsumed native oral beliefs into biblical, theological and Classical stories adopted from Europe.

Despite this blending of old and new, the position of the former gods and goddesses of the Irish, Scots and Manx, and whether they should be included or excluded from the new literary schema, was a matter of considerable debate among the scholarly classes. While some devout authors dismissed the pagan deities of their ancestors (and some contemporaries) as devilish phantoms, similar to those from the Old and New Testament, others looked to assimilate the pagan pantheon using biblical rationalisations popularised by their peers in the continental Church. Traces of this enterprise litters the surviving manuscripts.

Consequently some early Irish texts presented the Tuatha Dé Danann as “fallen angels”, semi-divine beings who had followed the archangel Lúcifir (Lucifer) in a rebellion against the Judeo-Christian supreme deity, or who had remained neutral during that conflict. Because of their unfaithfulness they were condemned to exile on the earth, their preternatural abilities stemming from their heavenly origins. In contrast other tales spoke of a rival and perhaps more influential interpretation suggesting that the Tuatha Dé were men and women who had left the biblical Gairdín Éidin (Garden of Eden) before the transgressions of Ádhamh and Éabha (Adam and Eve), and were therefore free from the stain of “original sin” visited upon the rest of humanity. Not unrelated to this was a theory presenting the Tuatha Dé Danann as a race of men and women possessing occult abilities (or later credited with such abilities) who had occupied Ireland in the distant past. Extending these two explanations a handful of accounts actually acknowledged that these ancient folk had been worshipped as gods by their descendants, though erroneously so as the writers were at pains to point out. In contrast to all of the above, a few religious scribes choose to accept the Tuatha Dé as part of the country’s cultural milieu without need for further comment or justification. For them the Tuatha Dé Danann, in all their manifestations, simply were.

The existence of remarkably similar origin-tales in the English, German and Scandinavian traditions, rationalising for a Christian audience the former veneration or existence of gods and other related beings through Old Testament borrowings, point to a shared practice amongst early Christian historiographers across western Europe.

The Name

It seems likely that the Celtic deities of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man were not known by the full name of Tuatha Dé Danann. The earliest recorded form of the title was Tuath Dé (also occurring in the plural, Tuatha Dé) which translates as the “People of the Gods”, “People of the God” or “People of the Goddess”. A possible clue to the original meaning can be deduced from a Latin notation written beside one early text; “plebes deorum” translates into English as “people of the gods”. However, whether this was the universal view or the understanding of one or more writers remains a matter of much modern discussion.

What we can say with some confidence is that at a very early stage in the history of the Christian religion in Ireland the name, Tuath Dé, also became an ecclesiastical term for the Israelites, with the intended translation, “People of God”. This may have led to some confusion in later years culminating in a late 10th or 11th century attempt to clarify matters. This was almost certainly by one or more writers associated with a compendium of stories known as the Leabhar Gabhála Éireann, an unparalleled syncretic history of Ireland from the creation of the world to the Middle Ages, combining disparate elements from native, Judeo-Christian and Classical sources. The clarification came through the addition of a name to the title of the non-Israelite people and after this period the Tuath(a) Dé were more frequently described as the Tuath(a) Dé Danann.

Following conventional Irish language rules, the word Danann must be the genitive form of an original nominative noun (so in the Irish language the noun sionnach mean’s “fox” but the genitive version sionnaigh means “of the fox“). Taking Danann as the basis, linguists have worked backwards towards a theoretical name, *Dana (in Old Irish *Danu or *Donu). This makes the Tuatha Dé Danann “…of *Dana“. Unfortunately this word actually exists nowhere in Medieval Irish literature. Instead, and quite ungrammatically, Danann is itself sometimes used as the proper noun. This is why we encounter a female character called Danann – occasionally spelled Dianann – in some relatively late stories. Perhaps significantly these occurrences are invariably in relation to tales of the many-authored Leabhar Gabhála Éireann referred to above. Adding further mystery Danann is actually spelled as Donann, with an “o“, in the earliest manuscripts. While this could be ascribed to scriptural errors and variant spellings it gives the impression that there is something amiss with the full title of Tuatha Dé Danann.

Several suggestions have been offered to deal with this conundrum. For many years scholars pointed to the word dán “skill, art; craft” (as in the title Trí Déithe Dána “Three Gods of Art” applied to the Tuatha Dé brothers Goibhne, Creidhne and Luachta) and argued for this as the base root of Danann. While some support can be seen for the idea given the emphasis placed on the Tuatha Dé’s association with arts and crafts by early Irish and Scottish writers most modern scholars believe it to be linguistically untenable. On the other hand a rather convoluted derivation of *Dana (gs. Danann) from the name of another early female figure, the obscure if seemingly important *Ana (gs. Anann) – in Old Irish her name would have been *Anu – does have some grammatical weight in its favour. This theory suggests that Tuatha Dé nAnann erroneously developed into Tuatha Dé Danann through the eclipsing of the “a” sound in *Ana and the rolling together of Dé and Danann. Unfortunately that leaves the question of the original spelling of Donann unanswered.

A more recent derivation pointing towards an Old Irish *don “place, ground, earth” and the related Modern Irish words domhain “depth, deep, abyss” and domhan “earth, world” has found some favour and would match, ironically, the Latin notations written by the monastic scribes describing the Tuatha Dé as “earth gods”. One speculative form of the original Tuatha Dé Danann name suggested by this theory would be Tuath Dé nDonann “People of the Gods of the Earth”.

Yet if a mythological character or actual goddess called *Dana did exist in her own right she would have had several close linguistic equivalents in the Celtic and Indo-European worlds, not least Dôn, an important if barely sketched female figure in Welsh literature and the mother of the Children of Dôn (a group often equated with the Tuatha Dé Danann in modern studies, though some have argued for a Welsh borrowing from Irish tradition in the early Medieval period). Why it took some centuries of literary development in Ireland for her name to be recorded and why it was written in the genitive form only, regardless of grammatical use, is still a mystery.

In summary then, there is little doubt that the indigenous Gaelic pantheon was originally known as the Tuath Dé “People of the Gods”, and under that title they were worshipped by the Irish, Scots and Manx. With the adoption of Christianity the early monastic scribes chose to call the Israelites the Tuath Dé “People of God”, a literal translation of the Hebrew tribes’ biblical title. It seems likely that this was done with some awareness of the confusion it would create with the older, non-Christian religious beliefs of the Gaelic peoples. Indeed, given the proselytizing nature of the early church it may have been a deliberate act of appropriation. In time the continued double-meaning of the name Tuath Dé (and the plural form Tuatha Dé) led the monastic writers assembling the stories of the Leabhar Gabhála Éireann to clarify the situation by adding a qualifying name to the title of the Otherworld people: no longer would they be the Tuath Dé, they would instead be the Tuath Dé Danann (or Tuatha Dé Danann).

Where Danann came from is, as we have seen, debatable but it is not unreasonable to suppose that there was an actual personage associated with the Tuath Dé and known as *Dana who was finally recorded in the literary tradition, albeit under the genitive form of her name (and with variant spelling). It may well be that she was a sort of “mother figure” in the divine community, originally a goddess of some note or an alternative name for a better known one already recorded by the scribes under an euhemerized form (perhaps the Mórríon in her more pacific guise, an arguable mother-goddess if ever one existed and who was probably identical with the female figure Bóinn). The present and popular modern Irish version of the name, Tuatha Dé Danann, stems from a late Medieval innovation. By the 12th century the supernatural race had made the literary journey from being the “People of the Gods” to the “Peoples of the Goddess *Dana”.

The Otherworld and the Otherworld People in Irish Mythology

The term Aos Sí or “People of the Otherworld Residences” refers to a race of magically-gifted men and women in the literature and folklore of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man who are almost certainly identical with the Tuatha Dé Danann. The name seems to be quite ancient, pre-dating the Christian period, but its meaning is tied up with the complexities of the word sí (Old Irish sídh, Modern Scottish sìth) in the Gaelic tongues.

The first – and probably oldest – meaning is Sí “(the) Otherworld”: that is the subterranean world of the Tuatha Dé Danann and Aos Sí in the native traditions of the Irish, Scots and Manx. This was originally the abode of the gods and their quasi-demonic opponents in the religion of the Gaels (hence the Latin “gods of the earth”). However it was also a type of afterlife for mortals, normally heroic ancestral figures or those favoured by the gods. It was reached through ancient burial mounds and caves, lakes and springs, or more supernaturally via sudden mists or visions (c.f the archaeological evidence throughout the Celtic world of presumed votive offerings deposited in the ground and in shaft-pits, bogs and lakes – gifts to the gods below?). Later it became associated with faraway islands reached by boat or ship. While this latter theme has been attributed to Classical (Greek and Roman) influences during the literary era it was just as likely a continuation of native traditions and such islands may have been a manifestation of the undersea aspects of the Otherworld. In later folklore mysterious coastal or overseas islands became more a prominent feature in recorded stories, especially in Ireland.

The second – and probably later – definition of Sí is “Otherworld Residence, Territory” (pl. Síthe “Otherworld Residences, Territories”). These Síthe were regarded as the otherworldly dwellings of the Tuatha Dé Danann and Aos Sí, while also providing access to their parallel kingdoms. They were part of yet separate from the Otherworld as a whole, and in the literature and folklore often represented the homes or lands of particular members of the supernatural community; and presumably at one stage the most prominent native gods or goddesses. Most Síthe were equated with the ancient burial mounds and cairns that dotted the landscapes of Ireland, Scotland and Mann (though the term was sometimes applied to other areas associated with the magical like notable hilltops, caves, wells, lakes and certain wilderness locations).

The majority of these ancient monuments dated from the Neolithic and Late Bronze Age, thousands of years before Christianity was imported to north-western Europe, and the memory of those who built them or what they contained had been blurred or lost many generations previously. Modern archaeologists believe the funeral function of the mounds to have been communal in nature, with interments over long periods of time, and there is a strong assumption that they were linked to “ancestry worship”. This probably contributed towards the evolving concept of such monuments in the ancient past as the dwelling places of ancestral kings or heroes – and the gods (it is worth noting that the Celtic inhabitants of western Europe were linguistically and culturally descended from the Neolithic peoples, and presumably inherited many of their oral beliefs).

It’s likely that the concept of the Tuatha Dé and Aos Sí living in different residences within the Otherworld also reflected the territorial divisions of Ireland and Scotland into separate kingdoms and lordships in the late pre-historic and Medieval periods. The idea may have been given impetus by the widely spaced locations of the burial mounds regarded as Síthe, suggesting an obvious equivalence with the widely-spaced dwellings and fortresses of the kings and nobility in the mortal world (especially if the great mounds were originally thought of by those peoples or tribes living around them as the abodes of their deceased ancestors). In a sense the Otherworld became an idealized version of the human world, distinguished by the magical aspects of its inhabitants, creatures and lands. These many layers of interpretation mean that the translation of the word Sí in the literature or folklore is often dependent on context, with many semantic ambiguities.

The Tuatha Dé, Aos Sí and Divine Castes

While in the early literature the Tuatha Dé and the Aos Sí are occasionally treated as different communities, in general it is understood that they are the same race. The term Tuatha Dé Danann is very much the formal and “literary” name while Aos Sí is a more familiar one (in a sense the Tuatha Dé became the Aos Sí). The argument put forward by a minority of modern scholars, that the Tuatha Dé and Aos Sí originally represented different levels or classes of gods in the pre-Christian pantheon echoes of which then survive into the literary tradition, remains largely unproven. However, it is worth noting that several references are made in the Irish texts to the rather tantalizing term Déithe agus Andéithe (Old. Ir. dé ocus andé) “Gods and Un-Gods” amongst the Tuatha Dé and Aos Sí. It is explained by the scribes in their Latin comments that the Déithe were their gods and the Andéithe their “husbandmen” (that is farmers, commoners and so on), giving the theory some credence, as well as hinting at far greater complexities of thought behind the character of the Tuatha Dé.

The relationship between the Tuatha Dé and the Aos Sí parallels to some extent the much more uncertain relationship between the gods (particularly the Vaner) and the Alver (“Elves”) in the traditions of the Germanic peoples, which includes the Scandinavians and English (all spelling in Modern Norwegian or Norsk Bokmål). Modern scholarly opinion generally regards the Vaner as a lower or lesser group of gods in the Icelandic/Scano-Germanic pantheon while the Æser represented the higher or superior group. The Vaner seem to have been more numerous than their occasional rivals in the Æser and may have had a closer association with agriculture, fertility and the natural world. This ties them to the Alver, the much debated elfin race of the Germanic peoples, and most writers believe that the Vaner and the Alver were identical, or at least originally so. Relatively late references to “Light Elves”, “Dark Elves” and “Black Elves” in the Eddas (the main mythological cycle of early Icelandic literature) are probably a contemporary misunderstanding. “Light Elves” are simply the Alver (Vaner) while “Dark” and “Black Elves” are the Dverger or “Dwarves” (who in turn may be related to the Jotne or “Giants”, the traditional enemies of the gods).

The Tuatha Dé Danann / Aos Sí and the Æser / Vaner / Alver can be understood then as loose equivalents of each other, a comparison which can be broken down further with the Aos Sí on one side and the Vaner / Alver on the other. Given the close Indo-European origins and geographical proximity of the Celtic and Germanic peoples it is hardly surprising that their mythological traditions are so similar. However, one should not carry such comparative extrapolations too far, important though they are for illuminating the mythological traditions of early Europe’s two largest cultural blocks. Peculiarities of language, culture, religion, geography and history also make for major differences.

Tuatha Dé Danann – Carn T, Cairn Loch Craobh, Sliabh na Caillí, Loch Craobh, An Mhí, Cúige Laighean, Éire (Íomhá: An Sionnach Fionn 2009)

Tuatha Dé Danann – Carn T, Cairn Loch Craobh, Sliabh na Caillí, Loch Craobh, An Mhí, Cúige Laighean, Éire (Íomhá: An Sionnach Fionn 2009)The Otherworld as the Afterlife

The Otherworld or Sí, while the domain of the gods and other supernatural beings, was also the world of the spirits of the dead: that is, in crude terms, the Celtic afterlife. It was where one’s ancestors dwelt after death and distorted memories of the role of the great burial mounds probably contributed towards this belief. However, in the recorded literature those mortals who visited or stayed in the Otherworld were primarily famous figures: legendary heroes and kings. Could it be that the Otherworld was not available to the ordinary people as a whole? Did they face a slightly less luxurious afterlife or no afterlife at all? Since early Irish and Scottish texts are mainly concerned with the lives of the noble classes (lay and ecclesiastical) it is difficult to know how much they reflect wider assumptions held in the pre-Christian societies of Ireland and Scotland.

It may be that one of the attractions of the new Christian religion for Irish, Scots and Manx converts was its promise of eternal life for all believers, regardless of one’s economic circumstances or status in wider society. The theory that Christianity began in the Gaelic nations as the faith of the lower classes (beginning with slaves from Romano-Britain and Europe) may be apropos here. Though it should be remembered that the qualifications for noble status amongst the Gaels were not simply about one’s bloodline or family but were instead more concerned with the possession of property and the system of clientism. As an Irish legal maxim has it, “A man is greater than his birth”, and commoners and nobles could rise and fall in status, and almost certainly did so.

It could be then that the ordinary people of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man outside the aristocratic families or learned classes could also expect a form of continued existence in the world beyond, though perhaps one less exalted than that of their noble peers. However this remains educated guesswork. Unfortunately it seems that the exact nature of the Celtic afterlife will remain one of several crucial areas of religious thought from pre-Christian Ireland and Scotland that (along with the beginning and end of the world) are lost or beyond conclusive reconstruction.

It is worth noting here that the Irish word for “Heaven”, Neamh, though now understood to refer to the Christian afterlife may originally have had a non-Christian meaning or association. However, this is a matter of (considerable) debate and nowhere in the early secular or religious literature of the Gaelic nations is the Otherworld referred to as Neamh.

The Fomhóraigh or Gods and Under-Demons

Aside from the gods represented by Tuatha Dé Danann and Aos Sí, plus some favoured or chosen mortals, the Otherworld was also home to the traditional rivals of the Tuatha Dé, the Fomhóraigh “Under-Demons” (sg. Fomhórach). The name probably originates from a conflation of the words fo (faoi) “under” (in the sense of “underneath, underground, subterranean”) and *mórach “demon, phantom” (pl. *móraigh), since the Fomhóraigh were viewed in the earliest layer of myths as living beneath the surface of the earth, and beneath the sea (this latter association influenced a later Medieval reinterpretation of the name as “Undersea Ones”, using a false etymology of fo- “under-“ and muir “sea, ocean”).

Despite the translation of “Under-Demons” it should be understood that these particular demons often appeared as simply another rival set of gods. Both the Fomhóraigh and the Tuatha Dé Danann interact, intermarry and share some names, titles and personages in common. Two extremely rare names for both the races that occurs in the very earliest texts illustrate this: Na Daoine Teathrach “The People of Teathra” and Fir Teathrach “Men (People) of Teathra”. Teathra (gs. Teathrach) was a Fomhórach who for a time ruled the Tuatha Dé in the more literary accounts of early Irish history, and the use of his name aptly shows the complexity of Tuatha Dé and Fomhóraigh relationships.

Because of the confusion that exists between the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomhóraigh it has been argued that they actually represent two broad divisions of the same divine community, the latter with a more hostile or violent character. Related to this is the suggestion that the differences between the two reflect class divisions in the population of the gods, with an aristocratic and scholarly caste sparring with a commoner or artisan caste (so reflecting the class system of early Irish society). Some have attempted to link this to the supposed divisions between the Tuatha Dé and the Aos Sí referred to above. However for some modern scholars the line between gods and Under-Demons (Under-Gods?) seems to go further than mere social distinctions, being a more fundamental, if fluid, one. They see both groups as separate races of the Otherworld, though ones that freely interact when not engaged in rivalry. What confusion there is, they argue, stems from the misunderstandings or redactions of the early Christian scribes, who overemphasized the monstrous nature of the Fomhóraigh and confused beings from both groups.

As indicated above with the examination of the Aos Sí, a comparison with the Germanic traditions of continental Europe and England can be very useful (some might say essential) for exploring the literary inheritance of the Celtic peoples. Taking the division of the Scandinavian pantheon into two closely related groups, the Æser and the Vaner (who were probably identical with the Alver or “Elves”), one finds some similarities with the Tuatha Dé and the Fomhóraigh. However a far closer comparison for the Fomhóraigh is to be found the opponents of the gods in the Scandinavian and Germanic myths, namely the Jotne. This title has been somewhat inaccurately translated as “Giants” and in modern folklore and retellings emphasis has been placed on their supposed monstrous size and nature (as with the Fomhóraigh). Yet in the original mythological stories the Jotne are often far from abnormal in physical form, let alone giants. Just like the Fomhóraigh they can appear as beautiful men and women, little different from the “gods” with whom they freely mate and produce offspring. Indeed at times it is difficult to discern where exactly the line should be drawn between “the gods” and “the giants” since such fluidly exists between them. Of course the very same thing could be said of the relationship between the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomhóraigh.

The suggestion that the literary form of the Fomhóraigh is simply a confused amalgamation of a lower class of gods and “anti-gods”, though not without merit, must be tested against the more plausible theory discussed above that what we have is an original – and actually quite intact – representation of a race of beings separate from “the gods” but yet closely related. This race can interact, interbreed and intermarry with the gods and though at times some may act in a hostile manner or take on a monstrous form they are little different from their divine opponents. This places them in much the same position as their Germano-Scandinavian equivalents, the Jotne.

The Definition of Divinity

This takes us to the nature of the gods and the much-debated concept of divinity. It is clear from the mythologies of the Gaelic nations (and related Celtic peoples) that the pre-Christian gods of the Irish, Scots and Manx were regarded as divine (because they were a class of supernaturally-gifted men and women), as immortal (because of their original and ever-living nature) and as progenitors (through their parentage of some mortal heroes or peoples). Beyond that it is difficult to go. Populist classifications of “sky-god”, “sun-god”, “nature-goddess”, etc. though clearly appealing to modern minds are simply wrong. To talk in these terms when describing Irish and Scottish mythological beings is to misunderstand the complex nature of the Celtic pantheon. Most Irish “gods” and “goddesses” don’t fit into the neat categories of modern classifiers because they were never intended to. The divine beings of Irish and Scottish tradition were multi-layered, multi-faceted characters with more than one attribute, and even shared attributes. There was no one“war god” because several shared that role. Yes, certainly, some beings were clearly more associated with particular aspects of life or nature than others (Gaibhne with smithcraft, the Mórríon with warfare and death) but this did not imply exclusivity.

Interestingly, though immortal the gods could die (or rather be killed). While this may seem like a paradox to contemporary minds it was far more common in ancient theologies. Likewise the habit of divine or supernatural beings engaging in shapeshifting, moving from “human” to animal form, or undergoing serial reincarnations, was perfectly acceptable. It did not, as is sometimes claimed, imply a general belief in reincarnation. There was none. Those who underwent shapeshifting or rebirths were divine beings or heroes with supernatural attributes. The pre-Christian Irish and Scots, as the Celts in general, clearly believed in an afterlife of sorts where one would dwell with one’s ancestors in the company of the gods. The question is to whom did this afterlife extend? The people as a whole or a privileged few?

Related Terms or Words

As well as the terms Tuath(a) Dé or Aos Sí the descriptions Fir Dé “Men of God(s)” and Fir Sí “Men of the Otherworld” were also used by the early redactors and seemed freely interchangeable. It should be also noted that a number of group names associated in the later literature with the Tuatha Dé (or Tuatha Dé characters) also occur in some very early texts, specifically the Fir Trí nDéithe “Men of the Three Gods”, and the Trí Déithe Dána “Three Gods of Skill” (later appearing, probably through accumulated confusion, as the Trí Déithe Danann “Three Gods of *Dana”). Two relatively old and popular words that have partially survived or influenced modern Irish terms should be mentioned here. Both mean “A dweller in a Sí; inhabitant of a Sí” and existed in the same literary context as the term Aos Sí.

The first is Sídhaighe, Síodhaighe. This has not survived into the modern Irish language as such but its influence (possibly via the word Sídheog?) can be seen in the contemporary words Sióg and Síogaí [see entries Sióg and Síogaí, below]. The second term remained in use right up to the Early Modern Irish period as Síodhaidhe. Under reformed spelling it became Síodhaí (gs. Síodhaí, pl. Síodhaithe). This word, now rarely used, is erroneously equated with the contemporary Irish term Síogaí “Elf, fairy” [See entries Síogaí and Síodhaidhe, below]. However Síodhaí is a more acceptable word for use when describing the beings of traditional Irish literature since Síogaí is a term more appropriate to the elf-like creatures of European folklore or Children’s fiction and is not an exact equivalent.

Irish Folklore, English Translations and Anglicised Forms

Later Irish and Scottish folklore, which had deviated somewhat from the early literary milieu, uses several terms to describe the Otherworld People as well as traditional ones like the Tuatha Dé Danann and Aos Sí. Most of these continue a seemingly old practice amongst ordinary folk of not referring to the Otherworld community by their proper name or title but in a circumspect way (though whether this is a post-Christian development or not is impossible to say).

In the English language, especially in recent times, a number of names have been used to describe the Tuatha Dé or Otherworld community of Irish, Scottish and Manx mythology. Common terms are: the “Fairies (or Faeries)”, the “Hidden People”, the “Otherworld People (or Folk)”, the “Ever-Living Ones”, the “Celtic Elves” and numerous others. Of these the “Otherworld People” is probably the most appropriate since it reflects the main aspects of the Irish and Scottish traditions (though colloquially “Fairies” will probably remain the most popular with all its unfortunate overtones). Other terms, especially those popularised in Neo-Celtic and Wiccan circles and some contemporary Fantasy fiction, are much more problematic with little or no veracity. Names like the “Sí”, “Shee”, “Shea”, “Dananns”, “Seelies“, etc. are very poor transliterations and should be avoided.

One of the sadder effects of the slow degradation of native Irish, Scottish and Manx cultures and their replacement with an Anglo-American approximation, has been the loss of the genuine imagery associated with the Otherworld People (be they the Tuatha Dé or Aos Sí). The use of the term “Fairies” as a translation in the dominant English language has resulted in 19th and 20th century European folklore images of fairies, elves, dwarfs, trolls and the like, supplanting much of the indigenous traditions. This has been exacerbated by the popular view of “fairies” created by children’s books, television programmes and movies. In contrast to nations like Greece, Italy, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark very few Irish people are aware of their own mythological or literary traditions nor are they taught them in most Irish schools. Scotland has an even worse record.

Recently a major Irish language news site described the character of Legolas from J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy series The Lord of the Rings as a “Lucharachán”. This word actually means a “dwarf or pygmy”, though it is usually translated as “Leprechaun“. By no stretch of the imagination could it be used as an equivalent to Tolkien’s Elves which, in fact, borrow heavily from Irish Mythology and the lore of the Tuatha Dé Danann. The term that should have been used was Síogaí “elf, fairy” or its like, a far better approximation. The complete lack of familiarity for most Irish people with their own indigenous traditions means few if any would have been struck by the incongruous nature of the use of Lucharachán for the English word elf.

Related to this one may note the false distinction drawn in contemporary English between “Fairies” and “Elves” in popular accounts of Irish and Celtic mythology. This is especially true of those that feature on the internet and in some less studious publications. In terms of their origins what we now call Fairies and Elves in a northern Europe context represent the same class of supernatural beings absorbed under the new Christian cultures of the early Middle Ages, and are common to the “post-pagan” Celtic and Germanic peoples. Obviously they are the pre-Christian deities, both pan-cultural and local, of the Celts and Germans when thought of in a collective or communal sense. Claims that “Fairies are Celtic” while “Elves are Germanic” represent a gross distortion of the facts. Both terms are equally applicable, if really required, though of course the word Elf is truer to Germanic linguistic history than Fairy which comes to us from Latin via the French language.

Further Reading

It has been noted many times that much of the information for early Irish, Scots and Manx literature, mythology and folklore, whether online or in printed form, is of little value for a genuine understanding or elucidation of the pre-Christian beliefs of the Celtic peoples of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Many of the “Celtic” books that have been published down through the years, even the most popular ones (or perhaps especially the most popular ones), are of mixed value. Sometimes, in the case of older academic publications, it is simply because the theories in them have gradually fallen out of favour, been replaced or disproved (yet publishers will continue to produce them, usually because they are no longer in copyright). More troublesome are the far greater number of books based upon populist stereotypes of the Celts. These works are usually informed by modern romanticism or ideas and concepts taken from the contemporary genres of Fantasy fiction, Anglo-Germanic folklore or children’s literature. Though undoubtedly profitable for author and publisher alike such books simply contribute to the spread of misinformation and confusion about the genuine nature of the various Celtic mythologies.

When it comes to information on the internet the situation is far worse, especially since what is available exists in such vast and readily accessible quantities (though much of it is repetitive). Most of it is out of date: antiquated theories or explanations taken from no longer copyrighted materials originally published in the 19th or early 20th centuries and posted or summarised on various websites, blogs or forums (often with a “Tolkienesque” veneer). In recent years the so-called “Celtic Reconstructionist” movements (Wiccans, Neo-Celts, Neo-Pagans, Druids, etc.) have become increasingly important in this area, though normally using a mix of the same dubious sources mentioned earlier as the basis for their “reconstructions”. Even Wikipedia, for all its vaunted new-found scholarly rigour, offers relatively poor fare.

However, a handful of sites, of academic or near academic quality, do exist online: and some of unexpected provenance. First and foremost are those offering original source materials.

The Corpus of Electronic Texts or CELT is perhaps the single most important resource for anyone wishing to know the ancient stories and histories of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Maintained by the University College Cork (and partly funded by the Irish state) the site contains hundreds of documents published online in both their original languages and with translations, and are available to people across the globe to view and study for free (and also to download!). Nothing else quiet like it exists on the internet and it is one of the academic treasure troves of the Celtic world. Though some of the older publications contained on the site have English translations dating to the late 1800s that would now be contested (in parts, at least), even the oldest works have a scholarly value that is second to none (and most have or will be updated). Furthermore many of the works on the site are no longer available or can only be purchased at great expense from specialist publishers.

The team behind CELT have also contributed to the creation of the extraordinary Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language or eDIL which is a searchable glossary of the Irish language for the period 700-1700 AD, and the Celtic Digital Initiative, which contains many interesting articles and studies. Perhaps of related interest is the enormously popular Bunachar Logainmneacha na hÉireann or Placenames Database of Ireland, containing a comprehensive list of placenames in Irish and English from across the island of Ireland, often with their origins, earliest appearances and translations. It is fully interactive, with mapping and data-search, making it a unique resource. For those wishing to see what the original stories of Irish myth looked like, in a quite literal sense, then Irish Script On Screen or ISOS is a must. It contains thousands of scanned images of medieval or later Irish manuscripts that anyone can view and is child’s play to navigate or search.

The private academic site *selgā (in German and English) is a catalogue of primary source materials for Celtic studies, providing links to many online resources (as well as printed ones) and is well worth visiting. Mary Jones is another well regarded Celtic site, though one aimed at a more general audience with a very wide range of out-of-copyright translations of Irish myths and sagas presented in scholarly form. Somewhat populist in places, and given to occasional bouts of Celtic romanticism, it nevertheless remains a good starting point for a tentative reader.

From a very different angle, but one focused much more on interpreting Irish (or more particularly Scottish) Mythology, is the website Tairis. It’s something of an unexpected delight since it represents one person’s interest or belief in “Celtic Reconstructionism”, usually something of a warning sign. However on Tairis it has achieved a remarkable degree of scholarly thought and the website contains some genuinely useful summaries of modern academic opinion. Fun, well written and above all intelligent, a careful reading makes it a great resource.

In a similar vein is the collaborative effort represented by Land, Sea and Sky. At first glance it may seem like another “neo-pagan” site but as with Tairis there is more of the enquiring scholar here than the born-again-druid. It contains lots of useful information, much of it remarkably free of mystical nonsense, and is a very useful primer for Celtic Mythology in general, even if some of the articles go too far in their suggested interpretations based upon the evidence available.

All these sites contain important links to other quality web sites, as well as bibliographical guides. For more on Irish language resources please visit here.

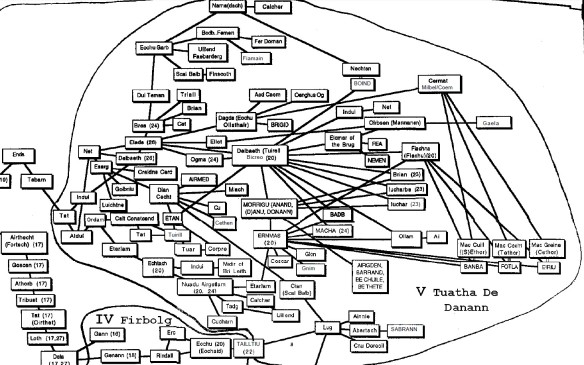

Family tree of the Tuatha Dé Danann showing key figures named in the Leabhar Gabhála Éireann, using Old Irish, Middle Irish and anglicised spelling (Íomhá: Lloyd D. Graham, 2002)

Family tree of the Tuatha Dé Danann showing key figures named in the Leabhar Gabhála Éireann, using Old Irish, Middle Irish and anglicised spelling (Íomhá: Lloyd D. Graham, 2002)Appendix I: Names of the Otherworld

Leaving aside the general name of Sí, or the many names of particular Síthe mentioned as being located in Ireland (and Scotland, the Isle of Man and elsewhere), a large number of titles, poetical and descriptive, existed for the Otherworld. They referred to the Sí as a whole or particular regions or aspects of the Otherworld. The most important were:

Má Mheallach “Delightful, Pleasant Plain”

Má Mhoin “Plain of Feats, Tricks”

Tír Tairngaire “Promised Land” (this is a direct translation of the Hebrew/Biblical “Promised Land” however it has recently been suggested that the term may be an original pre-Christian description for the Otherworld)

Eamhain Abhlach “Pair (Twins) of (Many) Apple Trees; (The) Apple-Treed Pair (Twins)” [eamhain “a pair (or triplet) born at one birth; a twin, one of two or three born together; a pair (of people or objects) / abhlach “of (many) apple trees; apple-treed”]

Tír na mBan “Land of the Women”

Má dhá Cheo “Plain of the Two Mists”

Tír na nIonaidh “Land of Wonder”

Tír faoi Thoinn “Land under the Wave”

Tír na mBeo “Land of the Living”

Insí Tuaisceartach “Northern Islands”

Teach Doinn “Tower of Donn” (Donn “Dark One”)

Má Fionnairgid “Plain of White-silver”

Má Airgeadnéil “Plain of the Silver-cloud”

Má Réin “Plain of the Sea”

Í Bhreasail “Island of Breasal”

Ciúin “Calm, Silent, Gentle (Land, Place)”

Iomchiúin “Very Calm, Silent, Gentle (Land, Place)”

Ildathach “Multicoloured (Land, Place)”

Inis Subha “Island of Gladness, Joy”

Airgtheach “Silver (Place, Land)” (alt. “Silver-house”)

Tír na nÓg “Land of the Young, Youth”

Má Teathrach “Plain of Teathra” [teathra “scald-crow, crow; sea, ocean”]

Appendix II: Names of the Most Prominent Tuatha Dé and Aos Sí Figures

This list is a sample of the more commonly encountered figures from the indigenous Irish, Scottish and Manx literary traditions presented in Modern Irish with alternative spellings, versions and sobriquets (please note that this list is not authoritative since there are no agreed modern spelling for several of the names featured).

Abharta

Abhcán

Abhean son of Beag-Fheilmhas

Áine daughter of Manannán / daughter of Eoghbhal, wife of Eachdha

Ailbhe

Aodh Álainn son of Bodhbh Dearg son of Eochaidh Garbh / the Daghdha

Aodh Caomh [gs. Aodha]

Aoibheall [gs. Aoibheaill]

Aoí son of Ollamhan

Aonghas the Mac Óg son of the Daghdha and Bóinn (Aonghas an Bhrú, Mac an Óg, Mac Óg, Macán Óg) [gs. Aonghais]

Airmheidh

Ana [gs. Anann]

Banbha, Éire, Fódhla

Beag

Bé Chuille daughter of Fliodhais (aka. Bé Théide)

Bé Chuama daughter of Eogan, wife of Eoghan Inbhir

Bébhionn daughter of Ealcmhar, wife of Aodh Álainn

Bile

Bóinn wife of Neachtan [gs. Bóinne]

Bodhbh Dearg son of Eochaidh Garbh / the Daghdha

Brea

Breas son of Ealadha and Éire, husband of Bríd (aka. Eochaidh Breas)

Brian [gs. Briain]

Bríd daughter of the Daghdha [gs. Bríde]

Cairbre son of Oghma and Éadaoin

Caor Ibhormeidh daughter of Eadhal Anabhail, wife of Anoghas the Mac Óg

Cearmadh Mílbhéal son of the Daghdha

Cian son of Dian Céacht (aka. Scál Balbh) [gs. Céin]

Clíona Ceannfhionn

Creidhne son of Easargh son of Néd

Daghdha (An Daghdha) (aka. Eocahidh Ollathair son of Ealadha son of Dealbhaodh)

Dana daughter of Dealbhaodh [gs. Danann]

Dian Ceacht son of Easargh son of Néd

Dealbhaodh son of Oghma son of Ealadha (aka. Tuireall) [gs. Dealbhaoidh]

Doireann

Eachne

Éadaoin wife of Miodhir [gs. Éadaoine]

Eadarlámh [gs. Eadarláimh]

Eaghabhal

Ealcmhar [gs. Ealcmhair]

Earnmhas father of the Mórríon, Badhbh, Macha [gs. Earnmhais]

Easargh

Éire, Banbha, Fódhla daughters of Earnmhas

Eithne / Eithle daughter of Balar, wife of Cian, mother of Lúgh [gs. Eithneann / Eithleann]

Fann daughter of Aodh Abhrath, sister of Lí Ban, wife of Manannán [gs. Fainn]

Fea

Fiacha mac Dealbhaoidh

Fionnuala

Fliodhais

Fuamhnach

Gaibhne son of Easargh son of Néd (aka. Gaibhleann, Gaibhne Gabha, Góban Saor son of Tuirbhe) [gs. Gaibhneann]

Iuchar

Iucharbha

Lí Ban daughter of Aodh Abhrath, sister of Fann

Lear [gs. Lir]

Lucahta son of Easargh son of Néd

Luachtaine

Lúgh Lámhfhada son of Cian and Eithne/Eithle daughter of Balar (aka. Lúgh Samhildánach, Lúgh Ildánach, An Scál) alt. spelling Lú [gs. Lúgha / alt. spelling gs. Lú]

Mac Cuill (aka. Eathar/Seathar), Mac Ceacht (aka. Teathar), Mac Gréine (aka. Ceathar) sons of Cearmadh Mílbhéal son of the Daghdha, husbands of Banbha, Fódhla and Éire

Macha, sister of Mórríon and Badhbh, daughter of Earnmhas

Manannán son of Lear, father of Áine, father of Mongán mac Fiachna, husband of Fann (aka. Oirbse)

Meas Buachalla

Miach

Miodhir son of the Daghdha, or son of Inneach son of Eachtach son of Eadarlámh, foster-father of Aonghas the Mac Óg, husband of Éadaoin and Fuamhnach

Mórríon wife of the Daghdha (An Mórríon) (aka. Badhbh, Neamhain, Macha) [gs. Mórríona]

Neachtan (aka. Nuadha) [gs. Neachtain]

Néd son of Inneach [gs.Néid]

Neamhain

Niamh daughter of Manannán

Nuadha Airgeadlámh son of Eachtach, son of Eadarlámh son of Ordán (aka. Nuadha Neacht, Neachtan, Ealcmhar) [gs. Nuadhad]

Oghma Grianaineach son of Ealadha and Eithle/Eithne, brother of the Daghdha, husband of Éadaoin daughter of Dian Ceacht, father of Tuire, father of Cairbre (aka. Oghma Grianéigeas, Tréanfhear)

Ruán son of Breas and Bríd [gs. Ruáin]

Sadhbh daughter of Bodhbh Dearg [gs. Saidhbh]

Tadhg [gs. Taidhg]

Tuirne / Tuire [gs. Tuireann / Tuireall]

Appendix III: Modern Irish Words and Terms Derived From Sí

The Otherworld-related words and terms below are taken from Niall Ó Dónaill’s 1977 Foclóir Gaeilge-Béarla, the standard, modern Irish-English dictionary. It should be noted, however, that there remains considerable debate about some of the English translations proffered, particularly for more traditional words or terms specific to Ireland’s culture.

Sí (gs. Sí, pl. Síthe) “Fairy mound” [alt. spl. Sídh, pl. Sídhe] [rel. Aos Sí “Inhabitants of fairy mounds; fairies”, Bean Sí “Fairy woman; banshee”] Note: “Fairy” is a particularly bad translation here, influenced by the English language, and the correct equivalent should be “Otherworld; Otherworld residence, territory”

The following words, though derived from the Irish Sí, are more applicable to the type of elfin or fairy-like beings that are encountered in modern Fantasy fiction, Children’s stories or non-Irish folklore. Their use in the context of the Irish “Otherworld People” is problematic.

Sián (gs. Sián, npl. Siáin, gpl. Siáin) “fairy mound”

Sióg (gs. Sióige, npl. Síoga, gpl. Sióg) “Fairy” [alt. spl. Sídheog]

Síogaí (gs. Síogaí, pl. Síogaithe) “Elf, fairy” [alt. spl. Síodhaí]

Síbhean (gs. & npl. Símhná, gpl. Síbhan) “Fairy (woman)”

Síofróg (gs. Síofróige, npl. Síofróga, gpl. Síofróg) “Elf-woman, fairy; enchantress” [alt. spl. Siabhróg]

Síofra (gs. Síofra, pl. Síofraí) “Elf, sprite; elf-child, changeling” [alt. spl. Siafra, Siafrach, Síodhbhra, Siabhra, Siabhair]

Appendix IV: Early Modern Irish Words and Terms Derived From Sí

These words are taken from Foclóir Uí Dhuinnín, the historic 1927 Irish-English dictionary, which uses the older unreformed spelling.

Síodh (gs. Síodha, Sídhe, d. Síd, pl. Sídhe, Síodha) “A tumulus or knoll, a fairy hill, an abode of fairies, arising from cairn or tumulus burial”

Doras an tSíodha “The tumulus entrance”

Lucht an tSíodha “The people of the fairy-mound”

Fear an tSíodha “The owner of the fairy-mound”

Aos Sídhe “Fairy-folk”

An Sluagh Sídhe “The fairy-host”

Bean Sídhe “A woman of the fairies”

Fear Sídhe “A man of the fairies”

Fir Sídhe (Fir Síthe) “Men of the fairies; phantoms”

Duine Sídhe “A fairy person”

Eachradh Sídhe “Fairy steeds”

Eoin tSídhe “Fairy birds”

Ceol Sídhe “A fairy music luring the unwary to their doom”

Liaigh Sídhe “A fairy doctor”

Leannán Sídhe “A fairy lover”

Ara Sídhe “A fairy-friend”

Ceo Sídhe “A fairy mist”

Solas Sídhe na bPortaighthe “The bog fairy-light, Will o’ the wisp”

Uaisle Sídhe “Fairy nobles”

Maithe Sídhe “Good fairies”

Síodhaidhe (gs. Síodhaidhe pl. Síodhaidhthe) “the occupier of a fairy-mound, a fairy chief; a fairy, goblin”

Síodhbróg (pl. Síodhbróige) “A fairy”

Sídheog (pl. Sídheoige) “A fay or fairy”

Fothsagán (pl. Fothsagáin) “A fairy, well-disposed towards mortals”

Siabhra (gs. Siabhra, pl. Siabhraí, Siabhraidhe, Siabhraighthe) “A phantom or spectre, fairy or goblin”

Siabhradh “A phantom, a spectre, a goblin; a spectre-like mortal”

Síodhbhradh (gs. Síodhbhraidh, Síodhbhartha, pl. Síodhbhradh, Síodhbhraidhe) “A fairy child or changeling”

Appendix V: The Celtic and Germano-Scandinavian Pantheons

A loose scheme can be devised showing the equivalences between the pantheons or Otherworld communities of the Celtic and Germanic peoples (represented by Irish and Norwegian terms).

Tuatha Dé Danann (“The Gods”) = Æser, Vaner, Alver (“The Gods”)

Tuatha Dé Danann (“Higher Gods”) = Æser (“Higher Gods”)

Aos Sí (“Lower Gods, Fairies, Otherworld People”) = Vaner, Alver (“Lower Gods, Elves, Light Elves”)

Fomhóraigh (“Anti-Gods, Under-Demons, Giants”) = Jotne (“Anti-Gods, Giants”)

Lucharacháin / Leipreacháin? = Dverger (“Dwarves, Dark Elves, Black Elves”)

Na Bánánaigh? = Valkyrje (“Valkyrie”)

? = Troll (note that the original trolls of Germanic and Scandinavian myth are very different from their folkloric descendants. While often monstrous in form they are exclusively female, closely associated with violent death, and are sexually promiscuous with both humans and giants. But not, significantly, the gods)

Glossary:

All spelling, names and terms in Modern Irish unless stated otherwise.

The modern long form of the name is:

Tuatha Dé Danann “Peoples of the Goddess *Dana”

The modern short form of the name is:

Tuatha Dé “Peoples of the Goddess”

The older (and probably original) forms of the name are:

Tuath Dé “People of the Gods (God / Goddess)”

Tuatha Dé “Peoples of the Gods (God / Goddess)”

The name is derived from the following words:

Tuath (pl. Tuatha), “people, tribe (or the territory, kingdom thereof)”

Dia (gs. Dé, pl. Déithe) “god or goddess” (Note: in Old Irish the word dé is dependant on context for its exact meaning and translates variously as “god, goddess, gods”; from dé is derived the Modern Irish word dia “god” and its genitive version dé)

*Dana (gs. Danann), the name of a female figure from early Irish and Scottish literature, generally assumed in modern accounts to be a goddess, though her name only survives in the genitive form Danann. The name *Dana is the proposed version of the original which was never actually recorded.

The Scottish (Gaelic) spelling of the name is: Tuatha Dè Danann

Aos Sí “People of the Otherworld (Otherworld Residences, Territories)”.

The name is derived from the following words:

Aos “People (Folk, Class)”

Sí “(the) Otherworld”

Sí “Otherworld Residence, Territory”

Scottish: Daoine Sìth “People of the Otherworld (Otherworld Residences, Territories)”

Scottish: Sìth “(the) Otherworld”, “Otherworld Residence, Territory”

Na Daoine Uaisle “The Noble, Aristocratic People”

Na Daoine Maithe “The Good People”

Scottish: Na h-Uaislean “The Nobles, Aristocrats (the Noble Ones)”

Scottish debased form: Sìthiche “Fairy, Otherwordler” (pl. Na Sìthichean “the Fairies, the Otherworlders”)

Scottish debased form: Sìth “Fairy, Otherwordler” (pl. Na Sìthean “the Fairies, the Otherworlders”)

© An Sionnach Fionn

Online Sources For The Above Articles:

- Warriors, Words, and Wood: Oral and Literary Wisdom in the Exploits... by Phillip A. Bernhardt-House

- Irish Perceptions of the Cosmos by Liam Mac Mathúna

- Water Imagery in Early Irish by Kay Muhr

- The Bluest-Greyest-Greenest Eye: Colours of Martyrdom and Colours o... by Alfred K. Siewers

- Fate in Early Irish Texts by Jacqueline Borsje

- Druids, Deer and “Words of Power”: Coming to Terms with Evil in Med... by Jacqueline Borsje

- Geis, Prophecy, Omen and Oath by T. M. Charles-Edwards

- Geis, a literary motif in early Irish literature by Qiu Fangzhe

- Honour-bound: The Social Context of Early Irish Heroic Geis by Philip O’Leary

- Space and Time in Irish Folk Rituals and Tradition by Lijing Peng and Qiu Fangzhe

- The Use of Prophecy in the Irish Tales of the Heroic Cycle by Caroline Francis Richardson

- Early Irish Taboos as Traditional Communication: A Cognitive Approach by Tom Sjöblom

- Monotheistic to a Certain Extent: The ‘Good Neighbours’ of God in I... by Jacqueline Borsje

- The ‘Terror of the Night’ and the Morrígain: Shifting Faces of the ... by Jacqueline Borsje

- Brigid: Goddess, Saint, ‘Holy Woman’, and Bone of Contention by C.M. Cusack

- War-goddesses, furies and scald crows: The use of the word badb in early Irish literature by Kim Heijda

- The Enchanted Islands: A Comparison of Mythological Traditions from... by Katarzyna Herd

- The Early Irish Fairies and Fairyland by Norreys Jephson O’ Conor

- The Washer at the Ford by Gertrude Schoepperle

- Milk Symbolism in the ‘Bethu Brigte’ by Thomas Torma

- Conn Cétchathach and the Image of Ideal Kingship in Early Medieval ... by Grigory Bondarenko

- King in Exile in Airne Fíngein (Fíngen’s Vigil): Power and Pursuit ... by Grigory Bondarenko

- Sacral Elements of Irish Kingship by Daniel Bray

- Kingship in Early Ireland by Charles Doherty

- The King as Judge in Early Ireland by Marilyn Gerriets

- The Saintly Madman: A Study of the Scholarly Reception History of B... by Alexandra Bergholm

- Fled Bricrenn and Tales of Terror by Jacqueline Borsje

- Supernatural Threats to Kings: Exploration of a Motif in the Ulster... Jacqueline Borsje

- Human Sacrifice in Medieval Irish Literature by Jacqueline Borsje

- Demonising the Enemy: A study of Congall Cáech by Jacqueline Borsje

- The Evil Eye’ in early Irish literature by Jacqueline Borsje and Fergus Kelly

- The Irish National Origin-Legend: Synthetic Pseudohistory by John Carey

- “Transmutations of Immortality in ‘The Lament of the Old Woman of B... by John Carney

- Approaches to Religion and Mythology in Celtic Studies by Clodagh Downey

- ‘A Fenian Pastime’?: early Irish board games and their identificati... by Timothy Harding

- Orality in Medieval Irish Narrative: An Overview by Joseph Falaky Nagy

- Oral Life and Literary Death in Medieval Irish Tradition by Joseph Falaky Nagy

- Satirical Narrative in Early Irish Literature by Ailís Ní Mhaoldomhnaigh

- Lia Fáil: Fact and Fiction in the Tradition by Tomás Ó Broin

- Irish Myths and Legends by Tomás Ó Cathasaigh

- ‘Nation’ Consciousness in Early Medieval Ireland by Miho Tanaka

- Bás inEirinn: Cultural Constructions of Death in Ireland by Lawrence Taylor

- Ritual and myths between Ireland and Galicia. The Irish Milesian my... by Monica Vazquez

- Continuity, Cult and Contest by John Waddell

- Cú Roí and Svyatogor: A Study in Chthonic by Grigory Bondarenko

- Autochthons and Otherworlds in Celtic and Slavic by Grigory Bondarenko

- The ‘Terror of the Night’ and the Morrígain: Shifting Faces of the ... by Jacqueline Borsje

- ‘The Otherworld in Irish Tradition,’ by John Carey

- The Location of the Otherworld in Irish Tradition by John Carey

- Prophecy, Storytelling and the Otherworld in Togail Bruidne Da Derga by Ralph O’ Connor

- The Evil Eye’ in early Irish literature by Jacqueline Borsje and Fergus Kelly

- Rules and Legislation on Love Charms in Early Medieval Ireland by Jacqueline Borsje

- Marriage in Early Ireland by Donnchadh Ó Corráin

- The Human Head in Insular Pagan Celtic Religion by Anne Ross

- Gods in the Hood by Angelique Gulermovich Epstein

- The Names of the Dagda by Scott A Martin

- The Morrigan and Her Germano-Celtic Counterparts by Angelique Gulermovich Epstein

- The Meanings of Elf, and Elves, in Medieval England by Alaric Timothy Peter Hall

- Elves (Ashgate Encyclopaedia) by Alaric Timothy Peter Hall

- The Evolution of the Otherworld: Redefining the Celtic Gods for a C... by Courtney L. Firman

- Warriors and Warfare – Ideal and Reality in Early Insular Texts by Brian Wallace

- Images of Warfare in Bardic Poetry by Katharine Simms

- Rí Éirenn, Rí Alban, Kingship and Identity in the Ninth and Tenth C... by Máire Herbert

- Aspects of Echtra Nerai by Mícheál Ó Flaithearta

- The Ancestry of Fénius Farsaid by John Carey

- CELT (Corpus of Electronic Texts) – published texts

- Mary Jones (Celtic Literature Collective) – translations

Printed Sources For The Above Articles:

- The Gaelic Finn Tradition by Sharon J. Arbuthnot and Geraldine Parsons

- An Introduction to Early Irish Literature by Muireann Ní Bhrolcháin

- Lebar Gabala: Recension I by John Carey

- The Irish National Origin-Legend: Synthetic Pseudohistory by John Carey

- Studies in Irish Literature and History by James Carney

- Ancient Irish Tales by Tom P. Cross and Clark Harris Slover

- Early Irish Literature by Myles Dillon

- Irish Sagas by Myles Dillon

- Cycle of the Kings by Myles Dillon

- Early Irish Myths and Sagas by Jeffrey Gantz

- The Celtic Heroic Age by John T Koch and John Carey (Editors)

- Landscapes of Cult and Kingship by Roseanne Schot, Conor Newman and Edel Bhreathnach (Editors)

- The Banshee: The Irish Death Messenger by Patricia Lysaght

- The Learned Tales of Medieval Ireland by Proinsias Mac Cana

- The Festival of Lughnasa: A Study of the Survival of the Celtic Festival of the Beginning of Harvest by Máire MacNeill

- Pagan Past and Christian Present in Early Irish Literature by Kim McCone

- The Wisdom of the Outlaw by Joseph Falaky Nagy

- Conversing With Angels and Ancients by Joseph Falaky Nagy

- From Kings to Warlords by Katharine Simms

- Gods and Heroes of the Celts by Marie-Louise Sjoestedt (trans Myles Dillon)

- The Year in Ireland by Kevin Danaher

- In Ireland Long Ago by Kevin Danaher

- Irish Customs and Beliefs by Kevin Danaher

- Cattle in Ancient Ireland by A. T. Lucas

- The Sacred Trees of Ireland by A. T. Lucas

- The Lore of Ireland: An Encyclopaedia of Myth, Legend and Romance by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin

- Irish Superstitions by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin

- Irish Folk Custom and Belief by Seán Ó Súillebháin

- Armagh and the Royal Centres in Early Medieval Ireland: Monuments, Cosmology and the Past by NB Aitchison

- Land of Women: Tales of Sex and Gender from Early Ireland by Lisa Bitel

- Irish Kings and High-Kings by John Francis Byrne

- Early Irish Kingship and Succession by Bart Jaski

- A Guide to Early Irish Law by Fergus Kelly

- Early Irish Farming by Fergus Kelly

- A Guide to Ogam by Damian McManus

- Ireland before the Normans by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín

- Early Medieval Ireland: 400-1200 by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín

- A New History of Ireland Volume I: Prehistoric and Early Ireland by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín (Editor)

- Early Ireland by Michael J O’ Kelly

- Cattle Lords & Clansmen by Nerys Patterson

- Sex and Marriage in Ancient Ireland by Patrick C Power

- Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe by H R Ellis Davidson

- The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe by Hilda Ellis Davidson

- Lady with a Mead Cup by Michael J Enright

- Celtic Mythology by Proinsias Mac Cana

© 2025 Created by Tara.

Powered by

![]()