HEREThe Origin and Lore of Fairies and Fairy Land

“Fairies were real once…”’ the lore of Fairies and Fairy Land

Spirit of the Night. Atkinson Grimshaw

Introduction

Etymology

Characteristics

Classification

Origins

Earlier Deities and Populations

Nature, Folklore and Fairy Tales

Fairies, Ancestors and the Dead

Fairyland

References and Sources Consulted

Introduction

The term ‘fairy’ is used to loosely describe a type of legendary or mythical being of romance and folklore. These unsubstantial creatures are often of diminutive size (Edwards, 1974). As spiritual entities fairies are considered to be supernatural, preternatural or metaphysical beings in possession off unbounded magical powers. In European folklore and fairy tales they are described as typically invisible or non-substantial spirits who live on earth in proximity to, or in association with mortal human beings. Fairies are presumed to possess knowledge of hidden natural powers which therefore “…corresponds with their power of making time appear long or short to those mortals who are lured into their company.” (MacCulloch, 1912).

A characteristic and distinctive feature is their whimsicality and mischievous and prankish behaviour (Hartland, 1891). Fairies can be of benevolent or malevolent, exerting good or bad influences over the lives of humans. Their magical attributes endow them with the ability to appear or disappear at will, or change shape into animal forms (Sayce, 1934). Fairy entities, in their restricted sense are unique in English folklore, though these non-human spirits abound Celtic and Germanic folk beliefs. Among European folk and fairy tales the fairies of French and Celtic romances are often merged with the elves of Teutonic myth. Similar stories of fairy-like creatures occur in other European traditions including the Latin and the Slavic, as well as their historical origin distilled from Celtic, Welsh and Breton medieval French romances and tradition. In many regions, including China, India, and Arabia with the Jinns, there are found beliefs in the existence of supernatural, sometimes dwarfish or pygmy-like ethereal entities. Their diminutive size and appearance was cultivated in response to the tales of Victorian ‘nursery tales’ read to children “…as a supernatural race existing in the fancy of the folk or North and West Europe.” (MacCulloch, 1912).

In the Late Middle English period the term faerie meant ‘enchanted’ or referred to enchanted creatures (Silver, 1999). In addition faerie implied the persistence of ancient religious beliefs replaced with the advent of Christianity (Yeats, 1988). In folklore faeries were believed to be a hidden remnant of a once conquered people with their contemporary image and origin enshrined and perpetuated by Victorian romantic literature and nursery stories.

Common literary impressions of fairy activity in their moonlight revelries, and of fairies of the household, the streams and woodlands. For some fairies are intimately connected with or originate with, the ancestral spirits coupled with the belief that the human soul was a mannikin. In some aspects the fairy in English lore was deemed a foreigner from France or Italy. For example the ambiguous position of Morgan Le Fee who “…was once Morgan the sea goddess, later euhemerised as a mortal queen with magical powers.” (Briggs, 1957), who was the controlling force over fairies because the predecessor to magicians and witches.

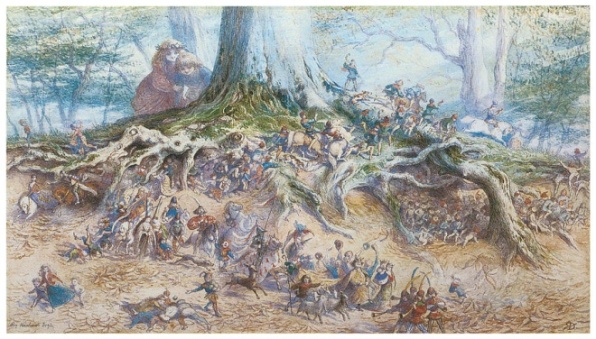

The Fairy Tree. Richard Doyle.

Etymology

The term ‘fairy’ originates with the Middle English word faerie, as well as fairie, fayerye and feirie, which were borrowed directly from the Old French faerie. In Middle English the word meant either enchantment, the land of enchantment, or the collective noun for those who dwelt in fairyland. In etymological terms ‘fairy’ is rooted in the word fay or fae from faery or faerie meaning ‘realm of the fays’. In modern English usage faerie became fairy and faie became fay which refers to a ‘fairy’. In other words the suffix ‘erie’ was attached the word ‘faie’ to mean a place or something found. For the Scots fey derived from fae became ‘faerie’ or ‘fearie’ meaning illusion or enchantment. The appellation erie eventually came to define a trade, craft, or place such as midwifery, fishery, cookery, thievery, and nunnery, and thence to wizardry, witchery, roguery and knavery.

In ethnological terms the exotic word pirie or peerie “…consequently Peribecomes in the mouth of an Arab Feti” (Edwards, 1974), which migrated to England via France to become ‘fairy’. In ancient Egyptian myth fairies paralleled the Seven Hathors or patronesses of childbirth, those regarded as ‘fairy godmothers’ (MacCulloch, 1911). The word feerie or fay-erie in modern French means land, realm, enchantment, or where the enchantment took place. The land of enchantment or fairyland is where dwell the fays or fee of medieval France. The faie or fee found in Old French originate with the fata of Late Latin meaning one of the fates or tutelary and guardian spirits.

The Riders of the Sidhe (1911). John Duncan.

Moreover, the verb fari ‘to speak’ implies ‘thing spoken’ or ‘decree’ and therefore a prediction, a prophecy linked to destiny or fate. In Scotland the spae-womanwas concerned with childbirth and omens. In other European tongues there are imaginary beings such as the fata of Italy, the fada of Portugal, the Provencal fada, the hada of Spain, and thence the fee of France (MacCulloch, 1912). In the Romance languages fata is a feminine noun which in the plural gives fatum or the ‘Fates’, making fays a late derivation from fatum. However, in the Romance languages entities called fays, fees, or fairies are not restricted to western European cultures. Such creatures as elves are from the word alfr and Anglo-Saxon aelf or alp which means genius, as well as the Scandinavian Norns and Vilas of the Slavs.

From Late Latin came fata rooted in fatum, and derived from fatare or feermeaning either ‘to enchant’, the ‘thing enchanted’, as well as trickery and illusions perpetrated by fays upon human perception. These deceptions and magical sleights ensured “…ugly crones are beautiful women or vice versa, fairy gold turns to dead leaves.” (Edwards, 1974). Hence fatare of Medieval Latin meaning ‘to enchant’ later exemplified an les dames faes or the ‘enchanted fairies of France’. Individually named fairies in tradition, myth and folklore include Abonde, Morgan le Fay, Avril and Viviane, together with banshees haunting woodlands and hills, and the fairy love of revelry that “…connects them with divinations in whose cult these were common, while the fairy moonlight dances may be a reminiscence of the cult itself…” (MacCulloch, 1911), echoing the sabbatof witches.

In classical mythology the Roman Parcae, or birth goddesses, were fata or fees. They were Nymphs and Fates known in Europe as descendants of the Germanic and Celtic Matres and Matronae. Also called eventually the ‘white women’ or the Bonnes Dames, Dames Blanches and Esterelle. Elsewhere these were the Be Find, Bonne Pucelles, and from the Latin the Pucellae and Bona Parcae. These matronae and others were originally trinities of goddesses concerned with springs, rivers, child-bearing and fertility (MacCulloch, 1911), the Parcae equivalent to the Roman Morai or Furies.

Titania and Bottom (1790). Henri Fuseli.

Characteristics

In the lore of fairies, and also in fairy stories, these spectral creatures were often viewed as possessed “…of a nature between spirits and men…” (MacCulloch, 1912). In general fairies had either a human-like appearance or were spirit-like creatures with a corporate semblance. In some shape or other fairy beings are a world-wide phenomenon who, wherever they occur, have some generalised characteristics in common. In many respects fairy beings resemble human beings. Euphemistically ‘faeries’ have been called the ‘wee folk’, the ‘good folk’, the ‘fair folk’, and in Welsh tradition the tylwyth teg (Briggs, 1976 a; 1976 b). Fairies can be solitary, such as the tomte in Sweden, or gregarious but usually “…not strongly individualised, and few of the Celtic fairies have personal names.” (Sayce, 1934).

Fairies have occupations and amusements, they have offspring and have fights (MacCulloch, 1912), and in folklore and fairy tales they share many commonalities in their relations to mortals, which fall into six categories. Firstly: (1) fairies help human beings; (2) fairies can also harm humans; (3) humans can be abducted by fairies for their own purposes; (4) fairies can exchange their own offspring for human babies and thus the belief in the ‘changeling’; (5) humans can be induced to visit fairyland and; (6) mortals can for a while have a fairy lover or mistress. Indeed, there is much in folklore that is concerned with protection against fairy malevolence, crediting these creatures with powers beyond that or mere mortals, and that resemble witchcraft, wizardry and practices of medicine men (MacCulloch, 1912). All occupations found in primitive communities were followed by fairies that included hunting, dancing, herding and farming, as well as being skilled smiths, shoemakers, weavers and spinners (Briggs, 1957).

One fear of fairy retribution is the abduction of women and children. This reflects a dependency on humans whereby young women and expectant mothers are stolen in order to nurse fairy offspring, and the fairy compulsion for human women to assist as midwives and suckling nurses (Rhys, 1901), or seduce mortal men and women. A stolen baby is replaced with a misshapen fairy baby, known in Ireland as the changeling. The changeling was a replacement for an abducted human baby. Old human females were also kidnapped and made to live as slaves in fairyland. The same could happen with the abduction of human midwives.

The Fairy teller’s Master (1855-64). Richard Dadd.

The popular conception of a fairy is that of a very small diminutive, sometimes tiny, creature resembling a pygmy. They are often shown as angelic, young or childlike, who are sometimes winged human-like winged sylphs. However, they can also be depicted as short, wizened troll-like gnomic figures with red or green eyes, or as tall handsome beings. Fairies have therefore a variable size, which they can change or appear as birds and animals (Sayce, 1934). In appearance some accounts describe the fairy as having the stature of a year-old child who nonetheless resembles a bearded old man, which is rooted in beliefs in ancestral spririts. In appearance and disposition sometimes they are beautiful, sometimes they are hideous (Briggs, 1957), as shown by spriggans of Cornwall, or the Northumbrian duergans. It is often the case of the female beautiful fairy being contrasted with the ugly male fairy, as with the Irish merrows.

The Fairy Ring (1850). George Cruikshank.

In folklore fairies are described as humanoid with magical powers and the ability to shape-shift, with a propensity for malice and mischief whose origins are even demonic. It is also believed that fairies cannot tell lies. It is among the fairy lore of the Celtic peoples there occurs the widespread theme of a race of ‘little people’ who were driven underground by invading tribes.

In Scottish folklore the good fairies, the Seelie Court, are well disposed towards humans, whereas the ‘unseelie court’ or bad and malicious fairies work their evil against mortals because some fairies are noted for malice and mischief. Therefore fairies hostile to people are feared because they ruin or steal crops, drink or food, tools and grain, who milk cows and ride horses during the night, blow out candles and disrupt households. Their pranks can be a punishment for a perceived wrong. Fairy assistance to humans and mortals is well attested with regard to home, hearth and farm. Although in general terms fairies are helpful, they are also mischievous and harmful to people if so roused. In the household they will do chores such as floor sweeping, dish washing, and tending the fire.

A Fairy Tale (1895). Arthur Wardle.

The Seelie Court are the good fairies of the Scottish lowlands (McPherson, 1929) who however can be hostile to humans if displeased. The unfriendly fairies are the Unseelie Court who are malevolent and concentrate their activities on harassment, injury, terror and even extermination of mortals. The Useelie Hostor the Host of the Unforgiven Dead are the Sluagh of the Scottish Highlands (Wentz, 1988). The Sluagh are therefore the evil ones. They are numbered among the trooping fairies, along with the Devil, the Dandy Dogs and the Yeth Hounds. Also with other creatures of ill-omen who hunt in packs, such as the Gabriel Ratchetts and the Welsh Cwn Annwn. There are also individual malevolent fairies such as the Duergar of the north country as well as the Black Dwarfs of English folklore, Germany and Scandinavia (Heslop, 1892). Similar to the Durgar are the Border Redcaps as well as the Dunters and Powries who are less murderous than the Redcaps.

Fairies are attributed with ability to become invisible at their own choosing, and affected by donning a magic cap, cloak or using certain herbs, and thus they can “…disappear, change their shape, and appear as human beings…” (Sayce, 1934). This fairy characteristic is bestowed by their power of glamour, shape-shifting and casting illusions.” (Briggs, 1957). The word ‘glamour’ was a Scottish term introduced into English literature that means magical, fantastic with the ability to juggle with the sight (Edwards, 1974). In other words glamour Is a magical charm cast by devils, wizards, a coup d’oiel in order to deceive the eye of the receiver. Indeed, humans have to be especially careful in their dealings with the fairies.

A portrait of a fairy (1869). Sophie G. Anderson

These diminutive beings are also deemed extremely long-lived if not immortal, as well as being “…dangerously amorous and have a tricksy love of practical jokes.” (Briggs, 1957). Their domain is regarded as being underground, a subterranean abode in tumuli, barrows, under hills or even beneath rocks and stones, and as ghosts “…haunt waste places, caves, rocks, ruins, and waterfalls, to have homes beneath lakes and to be associated with uncanny objects such as snakes, will-o-the-wisps, megalithic monuments…” (Sayce, 1934).

Puck and the Fairies (1850). J. N. Paton.

Fairies are often solitary spirits dressed in brown or grey compared to the popular conception of green apparel, skin and hair. Germanic dwarfs are commonly depicted wearing grey clothing. However, their clothing is quite varied though white is also popularly associated with fairies. Common also are red caps whilst hobs and brownies often clothed in rags.

Fairies, however, rarely harm mortal humans which includes those they abduct or lure to fairyland. Nonetheless a mistreated fairy is not incapable of retaliation by spoiling crops and setting fire to a household. The relationships between faerie and mortals can be further appreciated by the stories about fairy and mistress lovers which in literary terms often possess a drama and poesy. Such fairy stories have an established pattern of four main strands of: (1) a human loves a supernatural; (2) the spirit or fairy consents to the human dependent upon certain conditions and provisos; (3) the human eventually breaks the agreed taboo and loses his fairy lover, finally; (4) the lover attempts to retrieve or recapture the loved one, sometimes being successful. A similar set of conditions apply to fairy tales about fairy mistresses. A complication arising out of such an arrangement of a human-fairy marriage time that has lapsed. The sad result is that both time and age rapidly cat or liaison is the wish to catch up with the human lover.

Lily Fairy (1888). Luis Ricardo Falero.

All fairies are ascribed as being intensely enamoured of dancing, music, singing, feasting and revelry, that may persist as “…actual rites of orgiastic character…” (MacCulloch, 1912), and so have their origin in rustic festivals and agricultural magical practices.

An aspect of moral disposition of fairies is their being arrant thieves. Even good fairies purloin the property of mortals. Nonetheless they are also lovers of kindness, virtue, chastity, and cleanliness (Briggs, 1957). They take pleasure in playing tricks on humans such as taking food, spoiling the milk of cows, and minor mayhem if vexed. In other words they need to be placated if in a dangerous mood.

Fairies often help humans, distribute money and food to the needy, work counter-spells against witchery, and in the true spirit of the house fairy they will accept small rewards for their services (MacCulloch, 1912). Fairies also abhor greed and in medical matters are often resorted to by humans (Briggs, 1957), even though themselves they are dependent on human aid.

Folklore beliefs across the world attribute fairies to the detritus of ancient animistic beliefs. A spirit is regarded as a property of an inanimate object and archaic mythic figures are transmuted into fairy personages in later belief so “…fairy-lore must have developed as the result of modifications and accretions received in different countries and at many periods…” (Sayce, 1934). This links belief in fairies to the ancestral spirits of clan members. Ancestral spirits explains the beliefs in fairy subterranean dwellings as the domain of the dead, as well as the “…little difference in attributes, characteristics, and actions between Celtic fairies and Teutonic or Scandinavian elves, dwarfs, and trolls…” (MacCulloch, 1912).

Classification

Fairies are known by different names in various parts of the world, and fairy beliefs are complex, of great variety and antiquity, type and origin (Briggs, 1957). Various fairy folk exist in English folklore (Yeats, 1892), as well as including the elves, the abarativa, the Scottish wild horses or each uisge, the English Black Dogs, and the Irish sidhe. The fairy types resemble creatures from other mythologies in having numerous definitions. On other occasions these ethereal entities or sprites are referred to as magical, as goblins or gnomes. Some fairies are connected to specific places or localities such as the buccas in mines, or the Salamander in fire. In classificatory terms fairies have been separated into two large groups: (1) the fairy ‘race’; and (2) the solitary fairies. The fairy ‘race’ or ‘nation’ are located in ‘fairyland’ as a structured society. Included are the Irish ‘side’ or ‘little people of the hills’ and the Germanic dwarfs. The solitary fairies were connected to occupations, localities, and even particular households that include the water sprites and undines, the shoemaker leprachauns.

Another classification divided fairies into three species (Edwards, 1974) which were: (1) a dwarfish subterranean imp with benevolent magical powers, with green hair and clothes; (2) the solitary fairies. The fairy ‘race’ or ‘nation’ are located in ‘fairyland’ as an organised society. Included are the Irish ‘side’ or ‘little people of the hills’ and the Germanic dwarfs. The solitary fairies were connected to occupations, localities, and even particular households, that include the water sprites and undines, the shoemaker leprechauns.

Prince Arthur and the Fairy Queen. J. H. Fuseli.

Another classification divided fairies into three species (Edwards, 1974), which were: (1) a dwarfish subterranean imp with benevolent magical powers, with green hair and clothes; (2) tiny mischievous but protective household sprites associated with the hearth, and; (3) small ageless and winged females dressed in diaphanous material who contributed benevolently to humans, and who lived in fairyland. Another classification divided the English fairies into five classes (Briggs, 1957). These were: (1) the homely and the heroic; (2) the small fairy families or solitary fairy; (3) the tutelary fairies; (4) the nature fairies, and lastly; (5) the supernatural hags, monsters and giants. A urther group included the Morgan Le Fee type of magician.

Water Lilies and Water Fairies. Richard Doyle.

Contemporary and modern definitions of fairies have been derived from the fee of France, meaning a being of supernatural powers possessed of the boon of divination and influence over human destiny (Edwards, 1974). These French enchantresses carried wands, as did the Fates carry staffs, it is noteworthy that fairy-godmothers also carried a wand, thus the “…fairy godmother of the sophisticated French tales…is probably descended from the Fate of whom Fata Morgana was one.” (Briggs, 1957). By the middle-ages, around 1300, the three species or ‘races’ were distinguished. Firstly, the small type. Secondly, the dwarfish and goblinesque brownie type. Thirdly the taller stately attired damsel fairy. In modern parlance all fairies are casually referred to as the ‘little people’, hence “…distinctions have been lost, all ‘little people’ are discriminately fairies, and the differences, even the old names, are in danger of being banished into the limbo of forgetfulness by the quite artificial fairy of juvenile literary commerce, with gauzy wings and shirts reminiscent of the ballet.” (Spence, 1948).

Titania (1866). N. J. Simmons.

The most common fairy tradition in English folklore is that of the homely Trooping Fairies, who have farming connections, are variable in stature and can be either helpful or mischievous. The aristocracy of fairyland are the Heroic Fairies who live like the medieval nobility with a court and a king and queen. Typically of human size they hunt, sing, dance and engage in stately processions and revelry. Those of the Tutelary Type are attached to a human family as helpful diviners or omen bearing sprites. In this group are included the household brownie and the clan banshee. Such beings of this type are often the delicate silkie or brownie in Northumberland, which can become a boggart (Briggs, 1957).

The solitary and small family bands are independent spirits who frequent or haunt particular locations. Examples include the Border country Habetrot or spring fairy, as well as Irish cluricans and leprechauns. The small fairy family type are those who obtain human midwives for their family offspring. Nature fairies are widespread with the most common in English fairy lore being the water-sprites and the mermaid. The Scots have legends and beliefs in the loch living kelpie as well as the

The Visit at Midnight (1832). E. T. Parris.

Seas coast Nuckleavee. In the Highlands wanders the wintry blue hag known as the Cailleach Bheur, whilst in northern Britain there is Jenny Greenteeth who haunts stagnant pools (Briggs, 1957), in addition to the Scottish fruit protecting Churn-milk Peg and Awd goggie. Considered also is the guardian of wild animals known as the Brown Man of the Muirs.

Elves and the Shoemaker. By Folkard.

Another group, sometimes locally called ‘frittenings’ are the monsters, giants and devils who also include the supernatural hags who are less spiritual than the fairy demons. Such type of creature, boggart or hobgoblin are called according to locally braches, Padfoots, barguests, and brags. Quite often they adopt the form of an animal though they do not possess the ability to shape-shift.

Tuatha de Danaan.

Origins

In terms of origin fairies are a conflation of many strands and elements of folk beliefs, speculations about natural or hidden species, descendants of former subjugated populations, ancestral spitits and ghost, or fairy tales, myths and legends, literary compilations, as well as fallen angels and demonic creatures. In other words there is in fairy lore no single origin.

In Fairyland. Richard Doyle.

A number of theories have been postulated to explain the origin of fairies. Four main theories account for the origin of the belief. The concept may have developed from: (1) folk memories of earlier peoples conquered by the present inhabitants, hidden or lurking remnants, of previous populations lingering in caves or mountain recesses. Defeated or replaced peoples who prey on the occupiers in night-time raids and hence their supernatural reputations; then (2) degenerated deities of heroes whose stature has been reduced in importance. The allies of this group are the nature spirits; the (3) personifications of nature spirits originating in animistic beliefs of archaic peoples. The tree spirits and spiritually endowed inanimate objects. Such entities are anthropomorphised water spirits, undines, dryads, hill spirits, and the sidhe of Ireland. An example Queen Medb is the ‘queen of fairyland’ and euhemerised in the Irish epics. In group (4) are the ancestral spirits of the dead or the dead themselves who provide a strong and “…close association between fairies and the devil.” (Briggs, 1957), in the sense that fairies live below ground in tumuli and barrows as revenants, making fairyland a realm of the dead.

This explains the popular allusions to the link between devilish traits of horns, cloven hoofs and shaggy hides and images of nature spirits and folk gods. The association between demons and fairies may also originate with the peris or pieris of Persia whose not so wholesome activities were belied by their enchanting appearance, hence early beliefs in “…malevolent female demons…employed by the ruler of darkness to bring disaster to mankind, send comments and eclipses, prevent rain, cause failure of crops and spread famine and disease.” (Edwards, 1974).

The tradition of fairy superstition has no single origin, a number of causes being credited with causality, that include trance, dream states and psychic experiences. The persistence of the belief in fairies has been traced to “…animistic beliefs modified and altered in different ways by traditions about other races, by beliefs in ghosts, and in the debris of older myths and religions.” (MacCulloch, 1912). In England there survives little belief with the remnants consisting of mythological tales, heroic legends, fairy tales and ancestral echoes (Sayce, 1934). The existences accredited to fairies are contradictory. Some ascribe their living underwater, others to a subterranean existence, or in sacred groves. Wherever they occur fairies are mythical beings, the “…creations of fancy utilising existing beliefs, traditions, customs and experiences.” (MacCulloch, 1911).

The Quarrel of Titania and Oberon (1898). N. Paton.

There is an ancient and universal belief in the existence of an underworld principle. Howver, opinions as to its origin differ. Various explanations exist in folklore to explain fairies as the residue of doomed and rebellious angels. There is the fantastic association of fairies with cave dwelling spirits, and that “…fairy lore may therefore contain remnants of old mythologies…” (Sayce, 1934). The idea of the doomed insurrectionary angel is found in Celtic belief (Sikes, 1880; Keightley, 1900; Wentz, 1911). In Irish mythological tales fairies are referred to as the Tuatha de Danaan. Their origin is assumed to be derived from ancient goddesses, priestesses, nature spirits, nymphs, druidesses, the Fates (MacCulloch, 1911) making the fairies and the Tuatha the descendants of primordial gods and goddesses.

The Visit at Midnight (1832). E. T. Parris.

The idea that fairies are the result of a degradation process from ancient deities is not uncommon (Sayce, 1934). This is exemplified by the occurrence in goddess origin belief in fairy origin by the specific individuality of these spirits, even their names (Hartland, 1891). The concept of the fairy world is one that parallels the human that “…in many parts of the world centred about spiritual beings that bear many resemblances to our fairies.” (Sayce, 1934). In other words the otherworld social conditions are a reflection of our own. An example can be found in the Irish mythological cycle. The core of the myth is that the Tuatha de Danaan descended from the sky or, more likely, the northern islands. These Tuatha, the people of the goddess Danu, were defeated by otherworldly beings in battles, with further defeats by the ancestors of the modern Irish. The Tuatha forced to retreat, took to the ‘fairy mounds’, the ‘sidhe’, where they survived as ‘little people’, the fairies. In this underground haven or ‘world of spirits’, these people of the mounds or sidhe, existed in a land where everything was reversed, day was night, night was day, left was right and vice versa.

Fairies, as supernatural creatures were assumed to live in habitations underground, within the pleasant hills, called sidh or sith by the early Irish. The divine sidhe called the dinna-shee means “…people of the fairy mansions.” (Joyce, 1871) . Knowledge of these fairies known as the Tuatha de Danaan is very scant as are their chiefs called the Dagda and Bove Derg. The term originally applied to a fairy fort, mound or palace was sidh, and which over time came to mean a hill. During the passage of that time the word sidh came to be applied to the fairies themselves – fairy being sidheog pronounced sheeoge.

In the folklore of southern and eastern England faeries became known as frairies, feriers, ferishers, or as farises and even Pharisees. The word originated from the fear sidhean or ‘fair-sheen’ of Irish Gaelic. This shows a connection with the sidhe of the Celts (Edwards, 1974). In Ireland the Daione sidhe were not necessarily diminutive. In the Scandinavian Edda the ‘light elves’ lived in the realm of Alfheim, who were separate from the subterranean ‘dark elves’ or Dockalfar, who in turn were divided from the dwarf Dvergar. One fairy type, which was derived from, or even part of the household or ancestral spirits, was the brownie or house fairy. Brownies, in common with leprechauns, did not live in communities but often separate from the ‘trooping’ bands, who were the Sid in Celtic tales. The heroic fairies dwelt in splendour and luxury with names like the ‘fair folk’, the ‘still folk’ with a king and queen (MacCulloch, 1912), and whose names included Aine, Fionnbher, and Aoibhinn. In Old English ‘Fairy Farm’ or ‘Fairy Hall’ was from the word meaning enclosure, in other words haeg for feargh or pig sty. In English folklore the term faeger meant fair and eager or eye thus an allusion to beautiful eyes.

Under the Dock Leaves. R. Doyle.

Individual fairy names included Miala, Cliodna. Gwion, Huldra, Oberon or Alberon (MacCulloch, 1912). The Welsh fairies were known as the ‘Fair Family’ or Tywyth Teg who were smaller in size than humans. The image of these diminutive creatures was the beautiful appearance, golden hairs, benevolence and white apparel. This contrasts with the industrial and metal smith dwarfs called in Europe the nains, cluricauns, zvorge, draws dvergar, and thebergmanntein. Such etymology during the medieval period existed beside the fact that “…most Englishmen could not even read English and Latin was worse than double-Dutch, all learning was a mystery to them.” (Edwards, 1974).

Cont part2... HERE

© 2025 Created by Tara.

Powered by

![]()