The Origin and Lore of Fairies and Fairy Land Pt2

“Fairies were real once…”’ the lore of Fairies and Fairy Land

Earlier Divinities and Populations

Some elements of folklore have great antiquity and these contributions from all historical periods. It is already established that no particular source can explain the origin of belief in fairies.. It is known there was a regular antagonism between the role of the church and the fairy belief. The pre-Christian origin of fairy lore is shown by the great antiquity and distribution of fairy tales (Sayce, 1934). There are many archaic concepts associated with the lore of fairies which include shape-changing and extra-corporeal spirits. A parallel instance can be seen with witches and fairies. The connection between fairies and witches is a close one including the belief in “…bodily or spirit transportation though their air on the part of or by witches or fairies…” (MacCulloch, 1912). The belief in Gyre Carline is a Scottish fairy tradition of the elf-queen as the mother witch.

The Fairy Queen. J. N. Paton.

Fairies, as demoted or denigrated pagan deities may have been worshipped as minor goddesses, nature and tree spirits, as well as nymphs. For example water fairies may be remnant water spirits who, like the Scandinavian ‘elves’ and English ‘pixies’ are the “…trace of the ancient cosmology which divided the universe into various orders of being, gods, men and elves, dwarfs’ giants and monsters.” (Briggs, 1957). After the development of Christianity such beings survived, in a reduced state in the folklore beliefs and fairy tales, condemned as evil beings by the church. For some scholars many fairy stories were about real but euhemerised individuals or peoples (MacCulloch, 1912). The Victorians explained ancient gods and goddesses as metaphors for natural events accepted as literal happenings. Many references to fairies describe them as personifications of nature and abstract god-like notions. Therefore there was, in ancient Europe, an animistic religious belief coupled with memories of subjugated earth and mound dwellers.

If fairy belief suggests an archaic connection with real people, clans or cults, this “…probably goes back to the hostile relations which may have existed between Palaeolithic and Neolithic folk (MacCulloch, 1912). The widespread and one-time belief in the ‘little people’ has its origin in the pre-animistic and primordial communistic ideas, and are the true historical basis of belief in fairies. This is borne out by the folkloristic concept that fairies disliked the imposed civilisation on their aboriginal culture.

Leprechaun

Ancestral spirits are generally believed to be. Not only still members of the clan, but also to keep their human characters. These ghosts in the fullness of time were transmuted from folk memory into other forms. Fairies may have originated as the ancestral spirits or ‘ghosts’ of prehistoric clans “…transformed in popular fancy into actual supernatural people dwelling underground.” (Allen, 1891). If fairies are the ‘ghosts’ of earlier populations then the basis of fairy-lore consists of tales handed down of contacts with previous peoples. These peoples could either have been earlier inhabitants or immigrants. In time such peoples would have become mythical beings, no longer ghosts, no longer memories, but fairies. The remnants of actual historical populations.

For example the incoming metal equipped Celts would have conquered the stone weapon using people. The Neolithic people would have been hostile to their Celtic conquerors. In this scenario the defeated aboriginal population would have come to be seen as an underground living people, thus “…the inhabitants of the Neolithic tumuli grew to be regarded as a very tiny set of spirits…” (Allen, 1891). To the mind and thought of prehistoric people “…the distinction between living people and the ancestral spirits may not be so sharp as it is with us.” (Sayce, 1934). The folk memory of a pre-existing prehistoric people. Mistakenly believed to live in mounds and barrows, were transmuted into fairies. Therefore the possibility that such remote figures in time no longer seen as ghosts but as fairies.

Traditions, myths and legends about diminutive or pygmy populations exist in every myth and folktale, hence myths refer to “…former inhabitants of the country transmuted into mythical beings.” (MacCulloch, 1932). One theory is that fairies are a lurking remnant of primitive tribes and clans. In other words the “…small fairies derive from the memory of a conquered race of pygmy people…” (Briggs, 1957), and that the fairy superstition originated with the relationships between a dispossessed smaller population and taller conquerors. The implication is that fairies were once actual people. Therefore the question arises were fairies and earlier race of people?

ng

Morgan Le Fay (1864). F. Sandys.

It is established that the fairy superstition is widespread. Theoretically it may be that the origins of fairies are to be found with prehistoric peoples forced out my invasions and immigrants. The incoming invaders would have their own beliefs who would have possibly been welcomed by some of the existing people. In other words some ancient animistic beliefs would have survived if the invaders did not exterminate the original population (Sayce, 1934) but placated the encumbent ancient spirits as a policy. Many ancient pagan rituals and sites were Christianised on this basis.

Among the Celtic nations there exists a common theme of a ‘hidden people’, a race of diminutive people driven into hiding by invaders (Silver, 1999). There are many tales of migrating dwarfs and elfin creatures due to incursions of others (MacCulloch, 1932). The dispossessed disliked the human invasion which prompted retaliatory raids and revenge attacks, as well as unseen and nightly incursions There arose stories of theft, borrowing, kidnapping, and other sinister happenings that “…reflect incidents in the contact of conquered and conquering races.” (McCulloch, 1932). The resistance came to be regarded as a nation of spirits living in an underground otherworld of burial mounds or somewhere across the sea (Silver, 1999). Much of the lore of fairies and fairyland is rooted in the belief that fairies lived in duns, stone circles inhabited by ‘little people’, the devil. Picts, and giants.

Caliban

There is no evidence that tumuli were once the habitations of earlier populations. Neither is there for giant Cyclopes being the builders of ancient Mycenae. Some features ascribed to diminutive populations, which resemble those of fairies, do not apply to the Picts who were not a pygmy people. Indications are in fairy-lore, that the belief is the persistence of archaic cults rather than the survival of primitive peoples (Briggs, 1957). Is the belief in fairies derived from a belief in earlier divinities who themselves in origin were nature spirits who displayed fairy traits? For the ancient Brythons their later mystical divinities were once fairy beings, fairy kings and queens. Ancient divinities are still remembered in Italy who had fairy-like features exemplified by domestic Roman gods who resembled brownies.

Fairies on a shell. J. N. Paton.

Nature, Folklore and Fairy Tales

The supernatural being called a fairy is probably one of the most well known creatures in folklore and fairy tale. There are local and regional variations in folklore and “…stories of fairy-like creatures are to be found in nearly every part of the world…” (Sayce, 1934). There is evidence to suggest that the characteristics of dwarfish beings and fairies represent an earlier race of people. However, folklore is not a static subject set in stone. Such a simple and primitive belief in fairies can occur at different times and in different places. One theory claims that the origin of fairy lore is in fact animistic, and thus such ideas are “…the basis of the fairy creed, attached now to all kinds of supernaturals, now to traditions of actual men.” (MacCulloch, 1932).Within folkloric belief there is the phenomenon of associating the uncanny with the uncanny, the unusual with the unusual, and with beliefs about spirits and this “…general body of beliefs…tend to vary from one region to another, from one people to another.” (Sayce, 1934).

Modern perceptions of fairies as diminutive and fragile creatures is the responsibility of William Shakespeare and the Elizabethan poets. The play ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ is a case in point which was richly illustrated by Victorian artists. For example fairies were referred to as ‘little atomies’, as ‘small grey-coated gnats, or coachmen’, as well as nymphidae, ‘flower fairies’ or coachmen, ‘fluttering sprites’ who swim in the air and ‘ride the whirls of dust.” (Edwards, 1974). The spirits of the air were called sylphs from the Greek word silphe meaning a caterpillar. It is also a reference to the Latin term of silvestris nympha or ‘nymph of the woods’.

Morgan Le Fay (1862). E. Burne Jones.

With regard to elementals it was believed that fairies were an intelligent species distinct from angels and humans (Silver, 1999) and that elementals were thought by alchemists to be gnomes and sylphs. The concept that fairies are a component of ancestor cults is common among folklorists. Therefore it is argued that fairies were once ancestral spirits because many beliefs and customs agree with the theory.

Ancient peoples held the belief that inanimate things, animals and plants had souls of their own. It is not really clear what the relationship was between these nature spirits and ancestral spirits. Therefore, if the belief in fairies developed from belief in nature spirits, then fairies may represent either these half forgotten nature or ancestral spirits, perhaps both (Sayce, 1934). The development of fairies from ancient concepts of nature spirits is an animistic belief. Animism saw spirits as the denizens of stones, wells, streams, trees and groves who were regarded in some quarters as ‘fair folks’ or – ‘guid neebors’.

Ancient peoples paid homage to these earth and nature spirits who “…tenanted the little green knolls, spirits that that were usually invisible to the mortal eye, but at times made themselves known in human forms.” (McPherson, 1929). There developed over time the belief that “…earlier gods, connected with agriculture and growth, have for centuries been regarded as fairies…” (MacCulloch, 1911), with the activities significant at Beltane or May Day, and Samhain or November-eve (Wright, 1861). Some fairies were not connected with archaic deities but seen as direct descendants of the nature spirits of wells, trees and rivers. The Celts of Gaul worshipped fairy entities as niskas and peisgi who developed into water entities known as nixes and piskies (MacCulloch, 1911), which was an integral component of the nature worship of Teutons and Celts. In Celtic and Teutonic folklore and

No Way Out. Milixa Moron.

myth, as well as the southern European and Slavic, there is an abundance of water-beings of a fairy-like nature. Mermaids and Sirens plus the Welsh fairy-brides haunt the waters who emerge from the waters to prey on mortal men. In addition to Celtic lake and river fairies known as Morgans there are the Russian Rusalkas. Some fairies are therefore believed to be water spirits who can also be carnivorous blood drinkers and murderous wreckers. In contrast other water spirits are unselfish towards humans exhibiting solicitous behaviour, caring for health and making friends. Examples are found with the highland water spirits. However the Fideal, who haunts Loch na Fideil at Gairloch, is a malicious sprite who lures men down into the water to drown them. In England the equivalent is Peg Powler of the Tees and Jenny Greenteeth who haunts the streams of Lancashire (Grice, F. (1944).

The Celtic peisgi and the niskas have characteristics shared with Sirens as well as the northern Merrimanni, Wassermann, Nix, Nisse, Mummelchen and Stromkarl. Similar water fairies include the nymphs and naiads who adopt the form of cattle and horses. Again these are reminiscent of the water-horse or each-uisge, the kelpie and orfanc which are demonic types of archaic water-spirit in animal form. A further form of dwarfish being connected with the divine Norse Aesir in the Edda are the alfar. Though not water sprites these dark elves are allies and workers for the gods against their foes. These alfar themselves are possessed, like the fairies, of magical powers with the alfablot being the annual sacrifice to these beings.

Fairy tales tend to be narratively short about typical characters in folklore, including fairies, goblins, trolls, goblins, dwarfs. ogres and giants. The tales also include stories of gnomes and enchantments. Fairy tales, which however do not have to involve fairies, must be distinguished from other folklore stories such as moral tales, legends and fables about animals and beasts. Fairy tales can occur in both literary and oral form and whose history can be difficult to define. Legends as such tend to involve a belief in the truth of actual events. Perceived as narratives grounded in truth.

Fairy tales have been around for millennia having developed and evolved from ancient stories from many cultures with many variations. Moreover, the oldest stories are for both adults and children. An example can be seen with Children’s and Household Tales by the brothers Grimm. Fairy tales have been classified by folklorists in a variety of ways but no definitive and established meaning has been achieved by separate schools of thought. The fairy tales comprise a separate genre with the wider body of folktales. The definition of the fairy tale is disputed with some tales regarded commonly as including fables about animals together with other folktales. Both fairy tales and folktales contain animals and elements of the fantastic and the magical.

Fairies, Ancestors and the Dead

In folklore there is a strong association of fairies with the realm of the dead. There are many resemblances between ghost lore and fairy lore, even though at first sight fairyland seems as “…far as possible from the shadowy and bloodless Realms of the Dead…” (Briggs, 1970). Fairyland and the realm of the dead exist side by side, both are inextricably connected, interwoven as two strands of belief in ghosts and fairies. The fairy belief has much in common with ghost beliefs though the belief in fairies is not merely a derivation of the other. The conceptions of Hades and fairyland are interwoven with the King of Fairyland and the King of Fairyland.

In Christianity fairies were deemed to be ‘fallen’ angels, a class of the demolished from heaven, with the angelic in heaven the demonic in hell, and fairies in between (Yeats, 1988). In other words fairies were demoted from heaven but were not evil enough to be sent down to hell. A popular belief amongst religious Puritans was that fairies were entirely demonic (Briggs, 1976). One theory concerning folkloric belief and the spirits of the dead was that they shared some points in common. One belief was that fairies, if they were not actually the dead, were some sub-class of ghosts, or dead spirits. In many cases ghosts and fairies are one and the same in popular belief. One folklorist theory of ghosts and fairies (Briggs, 1957) proposes: (1) a universal interweaving of fairy and ghost beliefs, which includes the revelries of fairies and ghosts, the dead in fairy mounds, with hobgoblins and Halloween described as ghostly apparitions; (2) fairies are dependent on humans; (3) fairies are often

Midsummer Night’s Dream. P. Gervais.

said to be diminutive; (4) there are taboos against eating fairy foods. It is also dangerous to eat in Hades because both ghosts and fairies are subterranean beings (Silver, 1999), with some tales and legends telling of the sidhe, the burial ground domain of fairies and ghosts. Once again it is apparent that fairies and ghosts share many features in common despite wide variations in powers, characteristics, temperament, origin and type. Another aspect to consider about fairy origins is that an instance where supernatural ghosts also represent the “…contrary change by which ancient gods and goddesses are turned into ghosts…” Briggs, 1957).

The connection between fairies and ghosts is seen in the recurrent motifs of dangerous seasons and times including the twilight hours, Halloween, the festivals of Beltane, Midsummer, Samhain, Wednesdays and Fridays. Fairies and ghosts in common are believed active at certain seasons, and during the hours of darkness. All ghosts, and supernatural entities are repelled by iron, and with witches running water is a barrier to them, and the “…widespread and ancient belief ghosts love dancing, a characteristic fairy trait.” (MacCulloch, 1932). Moreover, many manifestations of inexplicable supernatural phenomena, cults of the dead, including poltergeists are blamed on fairy of ghostly origin.

The hobgoblin was once believed to be a household and friendly spirit, but which however became a malevolent entity goblin. Many hobgoblins are described as ghost-like or demon-like ghosts. Also house-fairies, elfins, brownies, kobolds and domovoys are “…almost certainly a transformed ancestral spirit, helpful and kindly…” (MacCulloch, 1932) who are assumed closer allies of the dead than fairies. Witches were believed to have fairy familiars who were the spirits of men believed to have died either violently or during the dangerous twilight ‘witching hour’. The distinction between bad fairies and good fairies is reminiscent of the distinction made between black and white witches in the popular imagination because “…in primitive times all the dead were fairies, and that Christianity has removed most of them out of the fairy power.” (Briggs, 1970). In earlier times having supposed dealings with fairies was punishable as witchcraft.

Not only were fairies and ghosts assumed more demonic or dead than angelic, both were believed to be both beneficial and harmful to humans. Both had the reputation of kidnapping children, ghosts and changelings were ravenous entities. Likewise, both fairies and ghosts could be repulsed or protected

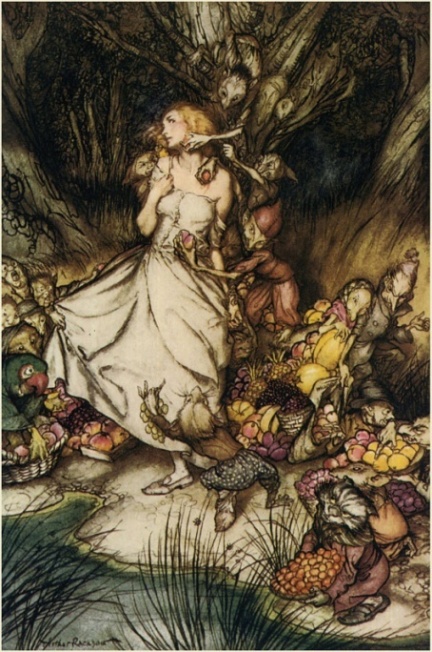

Goblin Market. Arthur Rackham.

Against using similar means. Ghosts and fairies “…as distinct groups in widespread tradition have yet curiously similar traits, and that there are similarly beliefs and customs regarding both.” (MacCulloch, 1932), is shown by a number of examples: (1) both are active at Halloween and May Day revelries; (2 both have offerings made to them; (3) both reserve the night for their dancing…in meadows; (4) both must, in common with vampires and witches, disappear at cock-crow or sun-rise; (5) fairies and ghosts have enchanted objects that mortal beings attempt to purloin or possess; (6) as do they share a dislike of un-cleanliness and untidiness.

In Irish tales fairies and the dead dance together on certain days, as well as being inhabitants of sepulchral mounds as fairy dead (Briggs, 1970). Indeed, the Irish banshee, or bean si and Scottish bean sidh means ‘woman of the fairy mound’ is sometimes thought to be a ghost (Brigggs, 1976).

Titania and Bottom. E. H. Landseer.

Nonetheless, the belief or concept “…that fairies or elves were small seems to have been brought to Britain by the Saxons.” (MacCulloch, 1932), not forgetting the hypothesis that the fairy-lore tradition of wearing green and white clothes are the colours of death (Briggs, 1970). In Ireland the term shiabhra is often used to denote a fairy, who is not only a supernatural entity inhabiting the nocturnal world, but also ghosts and phamtoms (Joyce, 1871). In Ireland the hideous churchyard goblin is referred to as a dullaghan.

In Welsh lore the Ellyllon are at times believed to be the souls of deceased druids (Kieghtley, 1898; 1900), similarly the fairy ‘hosts’ or sluagh are believed to be the dead. In folklore the “…strongest and most explicit connection between the Fairies and the Dead in England is in Cornwall.” (Briggs, 1970), including the buccas of the Cornish mines, the Devon pigsies or pixies, as well as Peg O’Nell. Will’o’ the’ Wisps have been considered to be the ghosts of unrighteous men, a concept because the “…largest body of belief regards them dead, though generally as some special class of dead.” (Briggs, 1957). The ‘hunt’ of the Celtic areas is believed to be the ‘fairy ride’ or fairies hurtling across the sky. Even English fairy lore is far less well documented than that found in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.

Fairyland

With regard to the location of fairyland it is usually regarded a separate region, subterranean and variously situated. Even though it is commonly believed underground it is at times located on an invisible island, or even underwater (Briggs, 1957). In folk belief this underground fairy realm was thought to resemble a pre-Christian ‘otherworld’ or Hades. In other words, in folk tradition the dead were often part of the fairy realm. The concept of the ‘otherworld’ in Celtic mythology was associated with the ‘Isle of Apples’ otherwise called Avalon or Elysium. Fairyland therefore was a non-theological heaven that was an aspect, a correspondence to purgatory or Hades, a type of fourth dimensional netherworld.

Midsummer Night’s Dream. Arthur Rackham.

Fairyland was thus a densely populated realm of the dead where in fact there was no illness, no ugliness, no aging, and no death. In fairyland, this land of the dead, where time was non-existent and characterised by lapses of a supernatural nature (MacCulloch, 1932). The ambience of this otherworld, this land of the fairies, was beautiful, pleasant and magical (Briggs, 1957). In terms of social organisation fairyland resembles feudal and medieval society ruled over by a king, whose queen usually dominated. The Fairy Queen or Queen of Elfin and her royal court, as part of the underworld were believed subject to the devil, where the king left management of the realm to the queen (MacPherson, 1929). Such social organisation suggests an echo of matriarchy. In Scotland witches were believed to be in league with the devil and the court of the Fairy Queen (Scott, 1802-1803; 1830). Fairies live like that of human mortals in fairy houses furnished with silver and gold. This contrasts with the individual or isolated fairies whose abodes were caves, wells, woodlands, bushes, mines, ruins, barns, stone circles and tumuli.

Puck and Fairies. J. N. Paton.

The entrance to fairyland was usually through a pit, pothole, cave, well, knoll, crevice, or hill top. The entrance allowed a living mortal to enter the ‘Otherworld’ or ‘Land of the Gods’ the access being known as the ‘Silver Bough’. The Irish Tuatha de Danaan supposedly lived in the sid or mounds and thus resembled underground people, troglodytes and Teutonic dwarfs (Kirk, 1893).

Fairies, as a species of beings, lived underground in their own dwellings or Elf-hills or Elf-hillocks, which were actually ancient burial mounds called by Elfin names, in the same way as flint arrow heads were called elf-bolts (Allen, 1881). In the lore of the ancient Celts the fairy folk, called the Aos Si, were immortal beings whose dwellings were prehistoric caves and barrows, as well as “…fairy greens, bright green circlets of grass, on which on moonlight nights, the fairies issuing from their subterranean abode, danced and made merry.” (MacPherson, 1929). The fairies were a merry throng who enjoyed immensely their gambols at the midnight hour, even though on occasions such pursuits were not all merriment, with supervening quarrels and sanguinary battles between fairy forts (Joyce, 1871).

The Irish Tuatha were associated with a number of realms of the underworld. Such supernatural places included Emain Ablach which meant ‘The Fortress of Apples’ or ‘The Land of Promise’, or ‘Isle of Women’. In addition Tir na nOg meant ‘Land of Hills’ and Mag Mell referred to ‘The Pleasant Plain’. In this realm the mythology of Irish fairies these superstitions “…no doubt existed long previously; and this mysterious race, having undergone a gradual deification, became confounded and identified with the original local gods…” (Joyce, 1871).

In another aspect Elfland was a counterpart to earth. In fairyland there were great feasts with rich repast. Much time was spent in dancing to music, with grand processions of white horses adorned with silver bells, and merry twilight hour revels around the entrance to their dwelling, the enchanted fairy ring (MacPherson, 1929).

The superstitions concerning the dead in Britanny are the same as those about fairies. Similarly the Breton tale of the fairy ‘washer at the ford’ has become a revenant (MacCulloch, 1912). In the Germanic folk tales, or marchen, fairies are also associated with tumuli or barrows and are known as ‘fairy hills’, ‘Elf Howes’ and ‘Alfenbergen’, the haunts of the interred (Dawkins, 1880). Again, an association of the dead with fairies in fairyland. In early and medieval Wales there existed the idea that the Faery King called Gwynn was associated with Elysium or Annwfn. In Highland and Irish folklore the ‘fairy washer’ was viewed as a ghost, a portent or harbinger, who warned against imminent death (MacCulloch, 1912). Again the Welsh aspect of hell and the ‘hunts’ for the wicked souls is called Annwfn. In fairyland, in the realm of the dead, time is a dream and passes imperceptibly (Hartland, 1891), with the food eating tabu based upon not consuming the ‘food of the dead’.

Morgan le Fay (1880). J. R. Spencer Stanhope.

There are many tales of the abduction of human beings by fairies, often of women to act as mortal midwives at the birth of fairy children. There are numerous analogous stories of an accidental visit, or by invitation, to fairyland. Abductees, especially children, are either lured, enchanted or seduced, in order to convey them to the realm of the fairies. Many stories relate of fairies searching for mortal women to nurse fairy children.

Lactating human mothers, who are always rewarded, or those with children, are taken because human milk is prized highly by fairies. The newborn human is especially at risk of fairy abduction. Fairy babies are substituted as a replacement which is then branded as a ‘changeling’. This belief in England appears to be a combination of Celtic ideas of the ‘people of the hills’ with the Germanic elf-dwarf concepts. Explanations vary but usually the fairy child returns to its own domain.

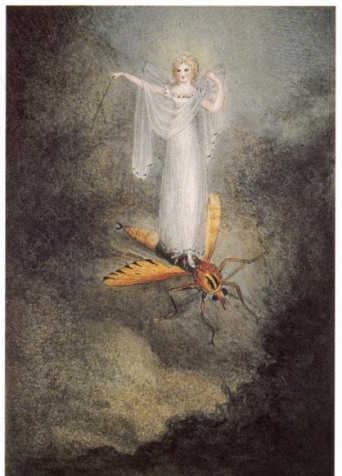

The Moth Fairy. Amelia J. Murray.

Finally, in connection with the fairy fear of iron, is the idea of a memory of Iron Age invaders. Similarly the assumed green apparel coupled with underground homes and ‘magical’ responses may well reflect an attempt at camouflage by the aboriginal, perhaps woodland or forest population. For the Victorians the Selkies were shape-shifting peoples of the seal, a belief attributed to memories of sealskin clad ancient maritime peoples. The folklore can be seen in relation to flint arrowheads called ‘elf-shot’. Elf-shot lore is possibly a relic or an echo of a time when flint using peoples lived in contact with metal-using people. Such a ‘memory’ may be a stone-age population transferred to fairies thus “…the raison d’etre of the elf-bolt is to be found in the fact that they, as well as many other spirits, used ‘invisible’ weapons to cause ‘stroke’.” (MacCulloch, 1932). The belief in fairies using ‘invisible’ weapons or using magic against animals and humans can also be related to elf-shot lore.

References and Sources Consulted

Allen. G. (1891). Who were the Fairies. Cornhill Magazine, XLIII.

Briggs, K. M. (1957). The English Fairies. Folklore. LXVIII. 31st March.

Briggs, K. M. (1970). Fairies and the Realms of the Dead. Folklore. 81 (2). Summer.

Briggs, K. M. (1976 a). The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature.

Briggs, K. M. (1976 b). An Encyclopaedia of Fairies. Pantheon Books, New York.

Campbell, J. G. (2005). The Gaelic Otherworld. In: Black (ed). Birkinn, Edinburgh.

Dawkins, W. B. (1880). Early Man In Britain. Macmillan, London.

Edwards, G. (1974). Hobgoblin and Sweet Puck. Geoffrey Bles. London.

Gaster, K. M. (1887). The Modern Origin of Fairy Tales. The Folklore Journal. 5 (4). 339-51.

Gray, R. (2009). Fairy Tales have ancient origin. Telegraph. 5.9.2009.

Grice, F. (1944). Folktales of the North Country. London.

Hartland, E. S. (1885). The Forbidden Chamber. The Folklore Journal. 3 (3). 193-242.

Hartland, S. (1891). The Science of Fairy Tales. W. Scott, London.Hastings, J. N. ed. (1908-1922).

Heslop, O. (1892). Northumberland Words. London.

Joyce, P. W. (1871). The Origin and History of the Names of Places. Dublin.

Keightley, T. (1850; 1900). The Fairy Mythology. Bahn, H. G.

Kirk, R. (1893). The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fawns, and Fairies. London.

MacCulloch, 1911 The Religion of the ancient Celts. Clark, Edinburgh.

MacCulloch, 1912 Origin of the fairies.

McPherson, J. M. (1929). Primitive Beliefs in the North-East of Scotland. Longmans & Co, London.

Newall. V. J. ed. (1980). Folklore Studies in the Twentieth Century. Brewer, Rowman 7 littlefield.

Popp, V. The Morphology of the Folktale.

Sayce, (1934). The Origin and Development of the Belief in Fairies. Folklore.

Scott, Sir W. (1802-1803). Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. Vols 1-3.

Scott, Sir W. (1830). Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft. John Murray, London.

Sikes. (1880). British Goblins.

Silver, C. B. (1999). Strange Places and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Conciousness. Oxford..

Spence, L. (1945). British Fairy Origins. Watts & Co, London.

Stith, T. & Thompson, R. (1972). Fairy Tale in: Standard Dictionary Of Folklore, Mythology, and Legend. Funk & Wagnall.

Stith, T. & Thompson, R. (1977). The Folktale.

Wentz, W. Y. E. (1988). The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries. Colin Smythe, London.

Wright, T. (1861). Celts, Romans and Saxons.

Yeats, W. B. (1892). Irish Fairy and Folktales.

Yeats, W. B. (1896). Fairy and Folktales of the Irish Peasantry. New York.

Yeats, W. B. (1988). A Treasury of Irish Myth, Legend, and Folklore. Gramery.

June 3rd 2015.

© 2026 Created by Tara.

Powered by

![]()